CW: This story starts out with a child who tries to “pass,” as many children do when young, in naïve admiration for some other ethnic group than their own, based on odd and sometimes quizzical preferences. But here, as I hope you will find, the attraction is mutual; the kinship of all is the goal, and I hope the “moral.”

It’s in the Blood

Johnny Beard was troubled in mind; Mrs. Carder was having thoughts. It was Mrs. Carder’s having thoughts that had made Johnny Beard troubled in mind. He was only six and a half, so his troubles usually seemed very large, but still came and went with the winds and the tides of the seacoast where he lived near Boddleston. The problems were only a few of the difficulties he’d had to face in his short life, but he was so used to having them by now that he hardly thought when something else went awry, but just viewed it as the way things usually went.

He had heard himself referred to as “an orphan,” so that was the title he obligingly bestowed upon himself when asked, though he wasn’t quite sure what all it entailed. He knew that it meant he had to live in Boddleston Commons Junior Housing with all of the others like himself, and he knew that all of them were supposedly waiting for a family from somewhere or other, anywhere, really, to sort them out from the others and take them to a “permanent” home. But having been left off when he was only three by a drunken mother already half-gone with her next offspring at the B.C., as it was known in town for short, he wasn’t quite clear either on what “permanent” meant. At first, he thought maybe the others who seemed happy to leave were being taken off and roasted and eaten by people who paid for them, as was mentioned of the unfortunate children in the storybooks featuring witches. He wanted to ask, but the workers and matrons were all very busy, some quite curt and harsh, others just careworn, so he decided to wait until the day when he could actually read to look up the meaning of the word “permanent,” if he could find a dictionary.

But his mental quandary came from eavesdropping, which they’d all been warned away from doing, as the workers often took their breaks and cigarettes and coffees or teas outside when it was nice; the benches and walkways were evidently there for all, but they always shooed the children away from these, because “you should be out in the grass playing.” He’d heard himself referred to in unfriendly terms soon after he got there as “Little Black Sambo,” and the name stuck for a while among his friends, even, such as they were. But since the children were of all races and ages, only the older ones of mean spirit seemed to know what this meant, so the name dropped away when he didn’t react, but just regarded them silently, with a shy, uncertain smile. Abigail Dawson, a thin, sickly little wisp of a girl with green eyes and flaxen hair whom he thought at the age of four that he might marry one day showed him the picture book with the story of “Little Black Sambo” in it, which was in their much outdated and not recently combed-through library.

From somewhere, Abigail had learned some rudiments of reading, and spent lots of time alone in corners with books, when not rousted out to play by attendants. She did her best to read him the story. It turned out that Little Black Sambo was quite a hero, because he had chased a tiger round and round a tree, until it had changed to butter, something edible and innocuous and delicious, or so he understood. But Abigail did tell him, in the nicest way possible, that it was still “very rude,” as she said, for others to single him out and name him that way, and that he shouldn’t stand for it, and shouldn’t “take it to yourself.”

Standing for whatever nonsense the world happened to take seriously about him wasn’t something he felt he could prevent, but on the other hand, not “taking it to himself” was apparently an internal matter, and totally up to him. So he allowed himself to fantasize about being “Gigantor John the Great,” tamer of beasts, winner of friends, and that was something he thought he might like to take to himself.

But one day, he overheard Mrs. Oxley, the head matron, saying in a puzzled way, “Well, of course, we can give you permission to adopt, or to foster either, some of our hardest to move cases. They would come faster to your hands than the others for whom there’s some competition. But why do you need them so suddenly, and so fast? And why six?”

Johnny peeked out from behind a chair where he was imperfectly hidden but had escaped notice thus far, to the other end of the entrance hall, where a jowly, stocky, older man stood passing a cap back and forth from one hand to the other. When the man began to speak, Johnny was enchanted: this was an Irishman! He had heard speech like that before from Gladys Kinnon, the night nurse, though she didn’t like him. But the softness of the sounds, and the rising and falling of the tones, yes, this was an Irishman, and moreover, he seemed sunny-natured, as he was ruefully smiling at Mrs. Oxley, who was quite serious and stern, and set upon her responsibility.

“Weel, ye see, it’s bit a bit like this. Me wife and meself had only the one but he had six. Six wee little ones, and all. But he and the lady his wife (who, to tell ye the truth, absolutely, Mrs. Oxley, was nothing of a motherly sort) thought to take them to the Shetlands for holiday, all of them, from the baby to the boy of twelve, and mid-ocean the liner sank, ye perhaps have heard something of it, the Rose Royal.”

Mrs. Oxley’s face changed, and she began to make sympathetic, murmuring noises. But he went on with his story, determined not to lose his persuasive energy, perhaps.

“And so, since our son Tim had a wealth to him that we’ve now got for ourselves, and only the two of us, and me wife and meself both grieving for the little lost ones, it seemed time to make good to society of it. And we thought that perhaps six of different ages might be what we were looking for.”

Mrs. Oxley now was even more eager to help, but helpless to acquiesce in some ways, due to her strictness to duty. “Ah, I see. But you can’t just pick out children like you can a new dresser or a matching end table, Mr.—what was it again, I’m sorry, the tale caught me up. Mr.–?”

“Carder, Robert John Carder.”

At the mention of his own name in the middle of the other man’s name, Johnny stirred, unintentionally attracting their attention.

“Johnny! What have you been told about eavesdropping?”

But the man held his hand out and lowered it to her, easing her fears of his displeasure, saying, “Johnny, is it? Why, a man after me own name! Now, Johnny, what are ye doing lurking round here instead of playing with the others?” The tone and attitude were friendly, but Johnny was once again stricken with his perennial shyness, and only looked up and down now and again from his feet to the man.

“Nothing to say to me? Now, why not, I wonder? Tell me, Mrs. Oxley, is Johnny free to come for just a leetle visit today? For lunchtime, perhaps?”

This flummoxed Mrs. Oxley. She sputtered and coughed a bit at first. No one, in the mostly white town descended from Northern European ancestors had ever asked to take Johnny home for a visit. But she didn’t want to stop a good chance, if there was one, so she said, “Well, he’s never been before. It’s the—the color thing, you know. Not many black families in Boddleston looking to adopt and the white families—well—” She paused. “He’s six, nearly seven. Does that make a difference?”

“Six, nearly seven! A great age! Johnny, man, now how do ye feel about cleekers?”

Wondering if this was a football team or a punishment of some kind like jail or some other thing he would be faulted for not knowing about, Johnny felt his face burn as he politely echoed, just barely heard, “Sir? Cleekers?”

“Six and a half, nearly seven, and don’t know cleekers? Johnny, your education has been neglected!”

Sad at the thought that he had once again been some sort of disappointment, and to this seemingly kind stranger, Johnny said, “Sorry, sir,” and prepared to sidle away.

“But ye can’t go the rest of your born days without knowing what cleekers are! Why don’t ye come home wi’ me for the lunchtime, and I’ll see that ye get safely back. You mightn’t believe it, but me wife is makin’ cleekers and soda bread as we stand here gaupin’, and just plenty for me and five or six young ones. No, she did say to bring along six, if I could be persuasive enough to take along a guardian or two of yours with them, Mrs. Oxley, so that ye would know they’d come to no harm.”

“Well…if it were only one, you could sign them out alone, as soon as you’d signed a few papers and looked at our list of policies and updates. But for six—well, there have been two staff members who haven’t had time off in a while, maybe they’d regard it as a bit of a lark, I don’t know. How about this? If I can get them to get the kids together in one of the vans, they’ll drop them with you and pick them up again on their way back from town. Assuming you live near—goodness, this irregular arrangement has me all confused. Where do you live, for starters?”

“Only around the turn of the bend from the farmer’s market corner, there just by the fruit stand. It’s a large, old house with a big bit of a backyard with a swing. That’ll have to be repaired, I’m sure, before hoisting of six youngsters all the time. Yes, I think we can do wi’ this.” And he winked at Johnny, who was very puzzled at a sudden feeling of butterflies in his chest, as if the heaviness that often resided there had hatched out of its chrysalises. But the man stood up to his full height, which was more than had first appeared, and said to him, very solemnly, “Do ye want to come, John?”

Not having realized that he had a choice, Johnny on the spur of the moment nodded until he felt his head might fall off, then, “Yessir!”

“Ah, that’s okay, now. To you, I’m Big John. And what do ye want me to call you, little man?”

“Johnny is okay,” and then he felt his face do two things at once. His cheeks split into a wide grin, and his eyes started to crinkle up and drop tears.

“Here now, me wife’s cleekers aren’t so bad as all that! And her soda bread has taken awards! There may too be carrots, or broccoli—now broccoli is what always makes me cry, Johnny, but the lady makes me eat it anyway, because it makes my hair curl. See my hair?” And he pointed to his mostly bald head, where two or three stray curly ringlets clustered around each side of his ears. “Why, look at ye, ye must’ve eaten a lot of broccoli, your hair is curls all over!” He came closer and bent down to Johnny’s height quietly and said in a confidential tone,

“Now, tell me, honestly, what do ye think of that broccoli, Johnny? As ye can see, Mrs. Oxley has gone to get me some papers, she’ll never hear a word against that deevilish green vegetable.”

“We don’t have it often,” Johnny began. Then, in a rush of confidence, “But it really would taste better, sir, with butter. Or maybe syrup?”

“Ah, Johnny. We’re deep into it now! Syrup will never pass Mrs. Carder’s home tests. But butter? I think I can do ye some butter, if it’s broccoli we have.”

“Does Mrs. Carder have a lot of home tests? I get nervous at tests.”

“Now, Johnny, my man, the tests are mostly tests for me, so I won’t get slop-handed. Or about food and cleanliness; well ye probably know how people get that are in charge. Just use your napkin a lot, and don’t burp or—excuse me—make that other noise that women are funny about, at least not in front of Mrs. Carder, ye know what I mean?”

Johnny, a little embarrassed, but taken with this odd remark, giggled and nodded. He’d never known adults like this at the B.C.

So, Johnny went, to his regret without Abigail, who was passing the week with a family interested in taking her to live with them. He would’ve liked to stay friends with Abigail, and he would never, ever be her enemy at any cost, but he knew the way of the lives that were chosen for them, so he squared his little ego and bore on, thinking maybe now that he could read and write they could still keep in touch, as adults did. And the day passed agreeably, with Mr. Carder and Mrs. Carder, and the other five children, who all were very loud and happy to be out, and sure of themselves, even though to Mrs. Oxley they were some of the least likely to get adopted. Johnny was in fact a bit ashamed to be with them, as they seemed coarse to him, and not gentle like Mr. Carder had been, so he was very quiet, and as he’d been more or less playfully told, used his napkin, and ate his meal with a good appetite, cleaning his plate carefully and completely the way the orphanage liked, but at a slow and deliberate pace so that he could watch his manners.

He’d naturally been curious, but the identity of “cleekers” became clear: cleekers were thick mackerel cakes, ones far tastier than the grey, dull flour-ish lumpy ones he’d had before. These tasted buttery (and indeed, the meal won his approval by its generosity of the butter on vegetables, bread, and in the cakes). They also had little flecks of what Mr. Carder whispered to them was parsley, an herb, while Mrs. Carder went to the door to answer a neighbor’s brief call. And there were some plainly mysterious flavors in them, tangible yet elusive, that he thought would remain with him forever; he felt serious regret at the thought that he must once again eat the flour-sack cakes made at the orphanage after this. The broccoli was bright green, buttery and with some salt, as were the carrots bright orange and likewise treated, the vegetables having some resistance to being chewed, yet all the more appealing for that, totally unlike the mushy, dull-colored vegetables he realized now had always been overdone. He was still finishing off his small bit of banana pudding when most of the others were at play in the yard before going back. And it was then that he overheard Mrs. Carder’s thoughts, the thoughts that she was having, was sharing, was questioning Mr. Carder about.

“But what kind of a boy is he?” She was standing somewhere out of his sight with Mr. Carder, in one of the two or three doorways leading out of the dining room, behind his head.

“A good boy, a shy boy. A lad like our Tim.” One more bite of banana, a bit of pudding. That was good ol’ Big John, taking up for somebody; maybe another orphan, like him. This made him inattentive for a moment, as a sudden dread that they might take the other boy and not him at all surfaced. He ate a little slower, carefully blotting his mouth between bites. He listened.

“But—he’s not—like us. Do you think people—your people—my people—what will people think? What will they say?”

“In this year of God? What the diddlededamn difference does it make what they say?” Mr. Carder sounded angry. He hoped they weren’t going to quarrel. Broccoli and cleekers were good, after all, but not that important. But Mr. Carder didn’t stay angry. He heard Big John say, “Now, Mary, don’t be fractious. Ye knew before they all got here today about all. I told ye all things that happened when I went.”

Something to do with one of them from B.C. Johnny felt uncomfortable, but unable to budge. He slowly dragged his spoon around the nearly empty pudding cup in a half-hearted attempt to let them know he was there, but they weren’t attending.

“But I thought we were going to get a whole bunch of them, six, we agreed.”

“Well, as ye’ve seen, manners and feelings about it differ. None have been promised anything yet. To most of these lot, it’s just a day’s outing. Not to be taken seriously. But I swear, I all but did promise him already.”

“Without talking to me first? You settled on one instead of six without talking to me first?”

“Not one instead of six, but maybe fewer. We raised our Tim by himself, and he was good as rain until he got that woman—well, God rest her, she’s with the fishes now, just like better before her, and all of them that we lost.”

“So, we’ll raise a spoiled darling?”

“So, ye think I would?”

“But how will we explain things about his race to him? I don’t know things like that! I want him, if we take him, to fit in with us and with his own. Nobody is unhappier than an outcast.”

Outcast. Another word like a title of a book. Johnny’s butterflies that had floated through his chest happily all day long now quietly and slowly sank back to the depths and settled on their old chrysalises wishing they could crawl back in, had never been awakened or flown up into the air so lightly. He knew now that they were talking about him almost certainly. The only other child of a different racial group than the Carders was Dorothy Canberez, and as she was a girl, that let her out of the conversation.

But thinking about book titles made him think of the lost or nearly lost Abigail, and he remembered what she had said to him, about not standing for other people’s making light or making fun of him, what she had said about not taking insults to himself. Figuring he had all but lost the day anyway, as Mr. Carder, whom he already loved as Big John, had told him Mrs. Carder was in charge, he made a decision to defend himself.

Swallowing the last bite of pudding then making a final blot of his mouth, he got up from the table and at the very last moment turned back, feeling a fatal burp coming. It passed quietly away. Mrs. Carder and Mr. Carder were still talking in the doorway as he approached, though when they saw him in front of them they both looked startled, as he had expected.

“Big John,” he said, in the most mature voice he could summon up to talk to a grownup audience, “I think I should explain.”

“Explain? And me lad, what would you like to be explaining, please? Finished your pudding and listening to conversations at the same time! I hadn’t thought it of you!” But even though Mr. Carder was being a little serious and severe, he still had a soft light in his eyes.

“Yes, you see, Mrs. Carder…I’m an Irish boy.”

“What did you say?” she answered, astonished, but looking from him to Big

John as if suspecting the two of them of something or other undefined.

Big John’s eyes were alight, but he waited. “Mary, I think…I think we may have to take that as a sign of acceptance of our invitation.” Big John and she seemed to be having a struggle with their eyes and expressions, and it didn’t end quickly. She eventually sighed.

“My dear young man,” she looked straight into Johnny Beard’s eyes and answered. “You may be many things; for all I know, you may well be part Irish, there are Beards in Ireland there, I know, and I’ve met a few Bairds who came from Ireland and not from Scotland. But don’t stand there with the very joyous crop of curls on your head and brown on your skin from Africa at some point and tell me that you aren’t a black boy, too, because one thing I don’t want you to be is a liar.”

“That’s me girl!” shouted Big John in a loud roar that made both the other two jump. “She’s already taken you in hand, Johnny me boy! Home test number one, no lies!”

“John, shhh! Behave yourself! The others outside are going to get hurt feelings if you don’t settle down. More of this later. You keep a close lip and a quiet heart too, Johnny Beard.” But she patted his shoulder as she passed him, on her way back into the kitchen.

And Johnny Beard did as she suggested, and found that not only he but Abigail and two others eventually found their way into the generous household of the Carders. For, it turned out that Abigail had bad luck with the family who at first found her so ideal: they had fed her a very rich menu, and when she became ill and threw up on their Aubusson carpet, they phoned to the B.C. to say that regrettably they couldn’t accommodate sickly children or badly behaved ones, and she should be picked up. And so, she came to the Carders’. Johnny’s luck, though, did not remain constant with regard to building his ideal family. Abigail drifted away from the family group in her later teens, when Johnny was nearly fifteen years old. They never heard from her again, which grieved Johnny and his adoptive parents both, and supplied a mystery for mournful meditations by Big John, who sometimes got a faraway look in his eye when he and Johnny were alone, as he didn’t like to discuss it before Mrs. Carder. She was sometimes tempted to be harsh about it, other times sad, but she and Abigail had had a very close connection until a falling-out about a particular boyfriend of Abigail’s, and Mrs. Carder seemed when at all vocal about it to waver between guilt for her own severity and reproaches for what she referred to as Abigail’s delinquency.

Johnny often thought to himself that he had traded the small but steadily burning candle of his life at the orphanage for the large and equally steady hearth fire of the Carders’, and though he regretted the one loss, he was happy that for a while they had been like brother and sister. He ruefully remembered his childhood dreams of marrying Abigail, and wondered if that had come to pass whether the Carders would have approved or disapproved. They had always done both the kind thing and the proper thing, well-mingled.

It was his turn at the last, when Big John suddenly became a widower, to do the kind and proper thing, by helping to manage the funeral arrangements of Mrs. Carder, and of himself offering to Big John to take on other roles as well. The older man had aged gracefully until the passing of his Mary, when he became abruptly so ill and even ill-kempt that the only thing that got him from morning to night was having his son with him while he ate and sat through the daylight hours, and even sometimes while he lingered at bedtime in his now-lonely poster bed before falling asleep.

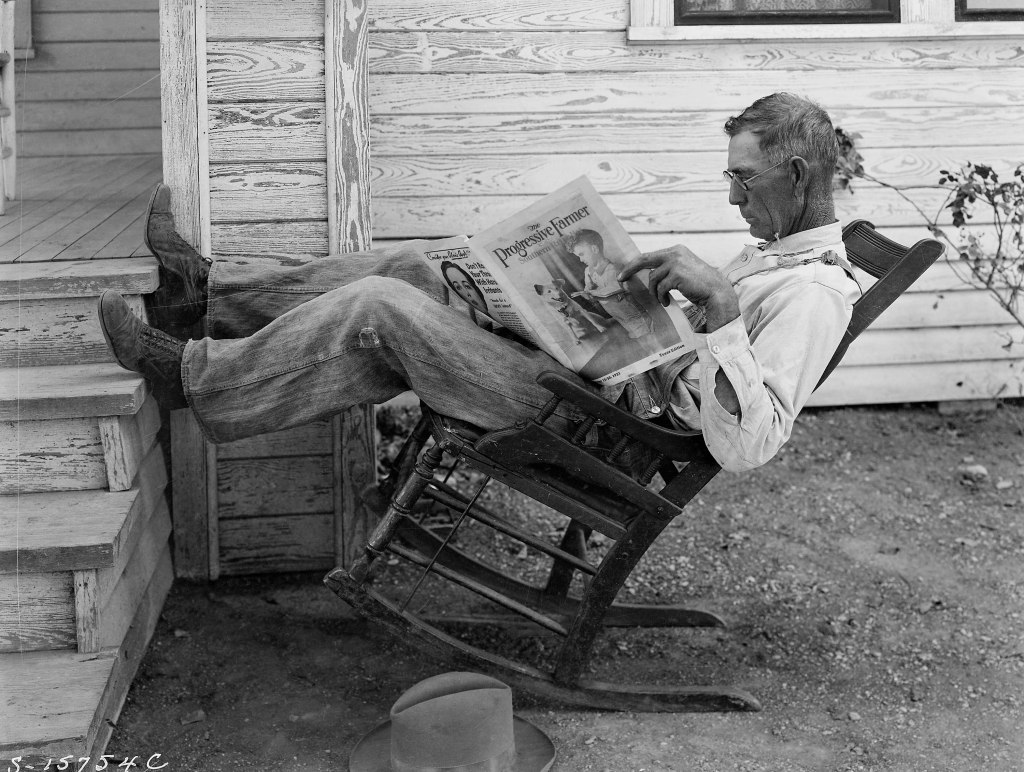

Johnny gladly for all they had done took time off from his management position at a local bookstore, where they were well-enough known as a family to be well-thought of by their neighbors. He made sure all was done for Big John until the day when he came in to find the old man dead in his rocking chair on the porch, where he liked to watch the birds at the feeders in the backyard.

On the day when Johnny helped carry his father’s casket to the graveside, an ignorant person who was unknown to the family, and who was merely an attendant upon someone else who had come to the funeral, noticed him. She tittered a little, which he heard but ignored, and remarked in a less than low voice to her companion, “Brown sugar?”

The embarrassed and annoyed friend said, “The son.”

Johnny thought of Big John and his likely amusement at such a trivial and minor person; remembered how he himself had once felt like a trivial and minor person; and turning to her, said “I’m an Irishman,” as much without expression as he could.

She looked totally bewildered, glanced at her friend for an explanation, who had none and shrugged, smiling his way.

“And this time, I’m really not lying.” They bore Big John on to the edge, where they lowered him in. When he threw in the first clump of dirt, Johnny knew then that it was really, really true that all men and women were equal.

Victoria Leigh Bennett

Bios and Links

Victoria Leigh Bennett (she/her).

Born WV, residing NE U.S. Ph.D., Cornell Univ. & Univ. of Toronto, English/Theater. Website: creative-shadows.com. Published (though OOP) books: “Poems from the Northeast,” 2021; “Scenes de la Vie Americaine (en Paris),” [in English], 2022, latter on website. Between Aug. 2021-Jan. 2024, Victoria has been published nearly 50 times in various publication sites, journals, websites, reviews, print journals, and newsletter poetry & fictions. She writes fiction/poetry/CNF/flash/essays. Victoria is one of the original organizers of the poets’ collective @PoetsonThursday on Twitter (now X), along with Dave Garbutt & Alex Guenther. Twitter (X): @vicklbennett & @PoetsonThursday. Bluesky: @katzrtops.bsky.social. Instagram: bennett.tori.758.

Thanks so much to Paul Brookes for publishing my story about Johnny Baird and the Carders on the day before the American holiday Martin Luther King Day. Encouraging brotherhood and improvements to the natural world, its survival, and proper human interaction with it has for long now been his mission.