Month: August 2022

We Build A City by Kinga Toth translated by Sven Engleke & Kinga Toth (Knives Forks Spoons Press)

InWe Build A Citythe Hungarian poet Kinga Toth reassembles, almost as an architect /builder, both language and genre: she is a ‘(sound) poet illustrator, translator, frontwoman, performer, songwriter’ who writes in Hungarian, German and English,living now between Hungary and Germany. Her work has won several important prizes. This book was originally published in Germany in 2019 and has been co-translated by the poet herself into English: the edition is sleek and elegant with a grey industrial landscape as its cover, however the dominant image, a rounded breast-shaped silo, hints at the deep gender concerns raised within.

Originally a philologist, her work signals a deep fascination with languageper se,

and she is not afraid to mould and transform it , experimentally stress its materials to breaking-point in order to createnew structures. This is an ambitious collection: the poems and graphics are collective in their range, remind us…

View original post 322 more words

Wombwell Rainbow Interviews: Glenn A. Barker

-Glenn A. Barker

a late developer in the treading and threading of formal and free verse, delves into the dislocated and saturated human dynamics of the way we live now, the age of anxiety. He also writes abstract expressionist wordscapes, rowdy cousin of the imagist style, and lighter sketches of contemporary life. He is yet to understand the world he writes about.

The Interview

- When and why did you start writing poetry?

I first started writing at the beginning of 2021, in the grip of another pandemic lockdown. The relentlessness of it all on our inner and outer lives tipped me into writing what I was thinking and feeling. Mental health is a fine balance; mine was a lingering low mood from household isolation. I felt that writing it down, whatever it was, would help me to get it out of my head.

2. Who introduced you to poetry?

My wife’s brother-in-law has been writing poetry for decades, and I had started to type up his fragmented work into something more presentable. However, it was Ian McMillan who really got me started, through a Twitter Lockdown Sonnet series. At the end of the video he said, “Have a go at your own sonnet”. So I did, and started writing lockdown sonnets.

3. How aware are you and were you of the dominating presence of older poets traditional and contemporary?

I think that for many people outside the poetry community, traditional poetry and the older poets remains the cornerstone of what a poem should sound like, and the themes it should encompass. I think I felt that too, until I started reading them and found nothing to draw me in. It was itself a wasteland; all far to erudite for me to feel any emotional connection with it. Finding the poetry of Simon Armitage was the breath of fresh air I needed to know that it didn’t have to rhyme, and I didn’t need a degree in Greats to understand it (or write it).

4. What is your daily writing routine?

I have no daily routine as such;. I keep a notebook to hand, but the scribbling is erratic. The more I look for something to say, the more it illudes me, so I wait for the muse to strike a feeling in me. The blank page is my enemy.

5. What subjects motivate you to write?

More than anything, I’m drawn to matters and mysteries of the psyche, the dynamics of human relationships and the state of our mental jigsaw in this age of anxiety. However, I can’t write like this all the time. I have a side line in impressionist wordscapes and abstract impressionist poetry. I also cover less weighty, more flippant subjects.

6. What is your work ethic?

I am retired; I have the luxury of being able to write any time the mood calls. My work ethic is flaky and has no pattern. It seems to work well that way. More than anything, I worry that I will run out of anything to say. The abyss follows me every time I finish a poem. Is it like that for everyone?

7. How do the writers you read when you were young influence your work today?

I didn’t read much at all when young, and it is only in the last thirty or so years that I have caught up with classic childrens novels, the 19th Century novel, and the works of Jane Austen. I still lean towards non-fiction. Catching up on fiction has been a challenge. However, there are two teenage formative texts that are an underlying foundation in my wordsmithing: the fact-fiction of Carlos Castaneda and the lyrics of Yes. I am a child of the Prog Rock wordscape generation.

7.1 What was it in Yes’s lyrics and Simon Armitage’s poetry that appealed to you?

Regarding the lyrics of Yes, there is a transcendent quality (a wisdom of the ancients perhaps) combined with a complex imagery, of storytelling in metaphor. The lyrics go far beyond the ordinary way of telling, inhabiting a language and landscape that uses a complex fusion of phrases and meaning that are difficult to explain, but paradoxically build into a picture, and impressionism, that seems to feel right. Just don’t ask me to explain; it seems more like a case of inner knowing. The following verse from Close to the Edge is typical of the Yes lyrical architecture:

“My eyes convinced, eclipsed with the younger moon attained with love

It changed as almost strained amidst clear manna from above

I crucified my hate and held the word within my hand

There’s you, the time, the logic, or the reasons we don’t understand”

The poetry of Simon Armitage appeals in that he manages to escape the confines of the ‘older poet tradition’, from the influence of his birthplace, childhood, backyard moorscape and contemporary approach to verse. ‘Magnetic Fields: The Marsden Poems’ is the volume that enabled me to make some kind of connection with him regarding a sense of place and time. The collection is shot through with childhood and place, like this verse from Privet:

“Because I’d done wrong I was sent to hell,

down black steps to the airless tombs

of mothballed contraptions and broken tools.

Piled on a shelf every daffodil bulb

was an animal skull or shrunken head,

every drawer a seed-tray of mildew and rust.

In its alcove shrine a bottle of meths

stood corked and purple like a pickled saint.

I inched ahead, pushed the door of the furthest crypt

where starlight broke in through shuttered vents

and there were the shears, balanced on two nails,

hanging cruciform on the white-washed wall.”

His poetry is rooted in the landscape and the natural, but is also infused with a modern, somewhat dry, humour and the occasional expletive that makes his work all the more approachable. Maybe there’s also the hint of the wistful, a nostalgic muck and brass view of life in and around the moors.

8. Whom of today’s writers do you admire the most and why?

I am not drawn to any particular contemporary writer or genre, preferring to take what the wind blows to wards me and piques my interest.

9. Why do you write, as opposed to doing anything else?

Sixty-plus years of life’s experiences have given me much to draw on. However, I am not a natural writer. Words are more a foe than a friend, so it has been a challenging journey and remains so; the words rarely flow as I would like them to. I think I have something to say and I think I have a voice that is me, and that probably keeps me going more than anything else, though I am not convinced yet.

10. What would you say to someone who asked you “How do you become a writer?”

This feels almost impossible to answer; like asking what musical instrument I should play. It must come from you, and if you want to say anything, go ahead, write it down. But you do it because you want to and you feel that you need to. You do it for yourself first, and if anyone else likes it, that’s a bonus. Remembering that Van Gogh did sell paintings in his lifetime, though not many, he also traded them. In the same way, how you become a writer also invites you to trade, or share, what you have to say, become part of community, develop your craft and perhaps in time become a ‘published’ writer.

11. Tell me about the writing projects you have on at the moment.

I have a reasonable body of work, good bad and indifferent. I keep everything I have written, so one task is to review poetry for publication and ‘improve’ it. I am revisiting the sonnets I wrote during my run-in with cancer. I am also testing the publication waters and getting used to more rejections than acceptances. Above all I am still looking for someone to read my work.

Miles Ahead

Seventeen years ago, slogging cross-country to Hythe, trouble with the MOD, the camps and ranges, then overnight on the coast, it was still winter, rain, wind and a black bin liner, more trouble in Lydd, and the last 10 miles with a split boot. That’s another story, an old story.

Seventeen years ago, slogging cross-country to Hythe, trouble with the MOD, the camps and ranges, then overnight on the coast, it was still winter, rain, wind and a black bin liner, more trouble in Lydd, and the last 10 miles with a split boot. That’s another story, an old story.

I still had the map that I used then, OS Landranger 189, reprinted with minor changes 2004. I took it out of the rucksack, it was the map of today’s walk, Ashford to Fairfield, a walk I had not taken before. It was not the journey of Wealden. It was a journey towards Wealden. An 85-tweet thread that unravelled on Twitter earlier this year, drafted en route to a performance of Wealden by Nancy Gaffield and The Drift in southern Kent, is now regathered (and lightly revised) as a post for the Longbarrow Blog (with accompanying photographs of…

View original post 501 more words

On The Royal Road: with Hiroshige on the Tōkaidō by James Bell (Shearman Books)

James Bell (1950–2021) passed away just a few months after submitting the manuscript of this collection to Shearsman Books. Some of his poems from the collection had already appeared inShearsmanmagazine, and the editor, Tony Frazer, eventually decided to publish Bell’s work together with the pictures of the woodblock prints from Hiroshige’s second Tōkaidō series. The poems are ekphrases that correspond to the pictures of the 53 stations that the artist drew after he had completed the journey from Edo (modern Tokyo) to Kyoto in 1832. He made sketches along the way which were later developed into successful prints that established his reputation. The first series ofThe Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidōwas so popular that Hiroshige published 30 more different interpretations of the Tōkaidō during his lifetime in both vertical and horizontal shapes. It was a long-lasting exploration of the highway with its commonplaces and its sense…

View original post 703 more words

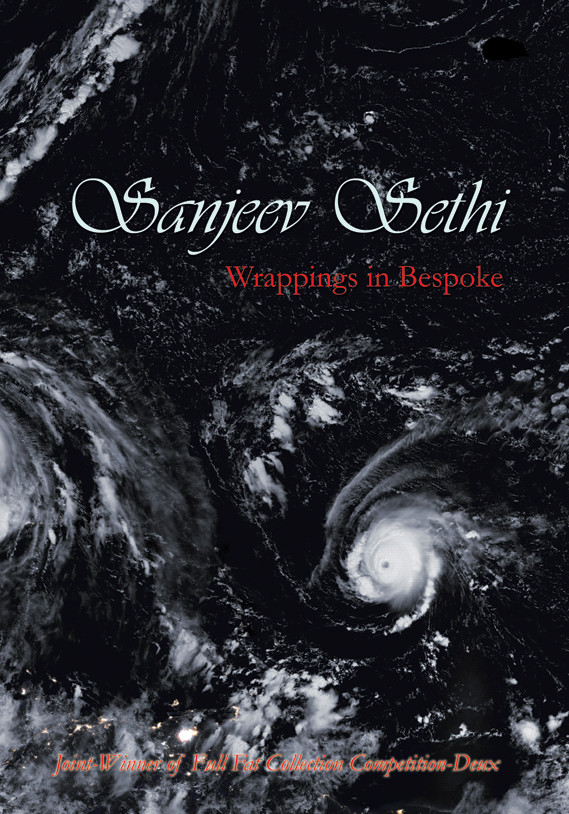

Review of ‘Wrappings in Bespoke’ by Sanjeev Sethi

Nigel Kent - Poet and Reviewer

Back in August 2020 my intention was to use this blog to draw readers’ attention to debut collections, but as time went on I decided to vary the content by occasionally inviting more established poets to share insights into their new works. Well, they don’t come more established than Sanjeev Sethi. The quality of his work has rightly earned international acclaim and Wrappings in Bespoke (Hedgehog Poetry Press, 2022) can only add to those accolades.

Perhaps the poem that provides the clearest insight into what to expect when one reads his newest collection is Wishes for a Child I Never Had. As well as being a statement of his view on the qualities that allow children to flourish in the ‘williwaw’ of life, I believe it also characterises the significant features of Sethi’s poetry. For example, in the second stanza he writes: ‘May the marrow in your bones…

View original post 1,178 more words

Wombwell Rainbow Interviews: Michael Mark

-Michael Mark

is the author of Visiting Her in Queens is More Enlightening than a Month in a Monastery in Tibet which won the Rattle Chapbook prize and will be published in 2022. His poetry has been published in Alaska Quarterly Review, The Arkansas International, Copper Nickel, Grist, Michigan Quarterly Review, Pleiades, Ploughshares, Poetry Daily, Poetry Northwest, Rattle, River Styx, The Southern Review, The New York Times, The Sun, Verse Daily, Waxwing, The Poetry Foundation’s American Life in Poetry and other places. He was the recipient of the Anthony Hecht Scholarship at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. He’s the author of two books of stories, Toba and At the Hands of a Thief (Atheneum). He lives with his wife, Lois, a journalist, in San Diego. Visit him at michaeljmark.com

The Interview

1. When and why did you start writing poetry?

I was born with a significant hearing loss (65% each ear) that wasn’t operated on until I was 11. I couldn’t hear others so I told myself stories – some were songs, some poems, though I didn’t know it then. Just keeping myself company. That, to a great extent hasn’t changed. It’s mostly why I write. Later I wrote love poems to my girlfriend in college, now she’s my wife. Pretty good feedback.

2. Who introduced you to poetry?

Formally, my college roommate, Kevin was the first one to really introduce me to poetry – Walt Whitman, Blake, Dickenson, Bob Dylan, Ginsberg, tons. He’d yell, “Check this out” and he’d read me some. And he could dance, man he could dance. Thanks, Quigley.

3. What is your daily writing routine?

Round the clock factory. I have a strong work ethic deep-rooted in fear I won’t ever get it right, I won’t fulfil the poem’s potential, I’ll miss another flitting by. I will track them wherever, play dead, bribe them, anything to be with those that hold that vibration that tells me this is vital, what I sense as “true” – a possible poem. So many fakers, decoys out there and I’m a sucker, fool myself a lot – half convinced I got a live one when it’s a gussied-up figment.

4. What subjects motivate you to write?

I work from innocence, unknowing, so curiosity is my engine, my headlamp. Words, syntax, diction, music, image, idea, lineation are the beams to explore with. I’m always open – object, nature, action, human beings – “what’s that?” The chapbook Visiting Her in Queens is More Enlightening than a Month in a Monastery in Tibet explores my mother’s Alzheimer’s so it’s about unknowing: who is this person, my mother – who is she now, and now? Change, mystery. This helps my work have many voices – as the speaker absorbs, engages with different states, worlds. I have heard that as a compliment and also an issue: “this is so different from other work – like, who are you?” I am just the radio receiver, if you like, no control over what’s coming over the airwaves, just an amplifier. I can hear the deli guy slicing meat say, “spicy mustard on that?” and be inspired, I can see my father dance to Sinatra or I could – though less likely, I could read a poem and be set off. I’m not very discriminating. It just has to have that buzz, that color, burnt taste of authenticity.

5. How do the writers you read when you were young influence your work today?

Writers are not my great influences though they do, mostly in form. Often, it’s what’s happening at the moment on the street, the radio, under the couch, in the trees, a blister on my toe. When I was young I listened to Dylan a great deal and his lyrics – well he’s Bob friggin’ Dylan – but I think of myself as a recorder, maybe a documentarian – as with this chapbook. I just watched my mom and our family and myself and took notes in lyric, formed them, listened to them again, reformed them, reformed them until what I ended up with might or might not be what happened. That doesn’t make them untrue.

6. Whom of writers do you admire the most and why?

Tony Hoagland who passed away a few years ago. He was a great, great master of voice, and brave and funny in a barely bearable way. I like Jayne Kenyon, Linda Gregg. Mark Doty’s a jeweller – I try to emulate his work but I can’t afford that Tiffany stuff. James Davis May – his book, Unquiet Things is so beautiful and honest – a new one is coming. Christian Winman, Mark Strand, the wizard Charlie Simic, Kathleen McGookey – wonderful prose poem writer. Russell Edson. Stephen Dunn. Mary Szybist how careful, gentle. Adam Zagajewski. Szymborska’s mystical everydayness. Sharon Olds’ effortless magical metaphors. Li-Young Lee, Bob Hicock, Mark Halliday. Claudia Emerson. Jane Hershfield. Mary Rufle. I got more if you have the time. I think I underestimated the influence of writers – thanks for helping me see that. I didn’t know.

7. Why do you write, as opposed to doing anything else?

I tried and I can’t do other stuff. I was told I was good at it when I was young and I hung on – and I love the relationship between my imagination and the other world – when they rub, clash, light a scented candle and leave the door open a crack. It’s the most exciting part of my day, except for pie.

8. What would you say to someone who asked you “How do you become a writer?”

Write, listen, write, watch, do physical labor, get hurt – not to bad, rewrite, rewrite, rewrite, rewrite – say No to anything else, almost anything. Look under the hood of the writing that makes you high – learn the machinery – the craft. Keep your enthusiasm as you realize you’re not there yet. Keep your innocence as you learn the transaction knowledge for inspiration might or might not be worth it. Write of yourself, that means how you hear it which will not be how others hear it and they will tell you to change it and sometimes you should. Rewrite it this way that way this way. Confuse yourself. Find honest good, really good, dedicated readers – listen to ½ maybe 1/3 of what they say.

9. Tell me about the writing projects you have on at the moment.

Now that Visiting Her in Queens is More Enlightening than a Month in a Monastery in Tibet is out, I have started three other projects – one is about the pilgrimage in Spain, Camino de Santiago that I have walked three times. It has a family aspect, too as I have walked it twice with my children at different times. Another project is a thing project, a refining of objects that we think we know but maybe not. Maybe not seems to be my thing. Thanks for asking me these questions.

10. How did you decide on the order of the poems in your book?

I was going for: order meets chaos and decide they might like each other, maybe have a future- so a hopefulness in catastrophe, that last scene in the movie, Thelma and Louise. The first poem in the book is expository, introduces the “her” in the book’s title by name and relation, and the speaker who is “visiting” her, also from the very, very long book title. That sets the sturdiness that’s birthed from the convolution of the book’s title. The chaos comes within the poems that were written as individuals, without a notion of being collected, over 5 years – and how they harmonize and clash with their neighbors. I wanted them in some chronology but not always linear. They are different glimpses of the same characters as they grasp at control through imagination and memory and the guts to get through the minute. The ending poems are about beginnings. I wanted to have some lightness, a melancholy magic.

11. What is the purpose of the precise domestic detail in the poems, such as opening a can?

Grounding, I think. The physicality of opening a can, cleaning an oven, is in argument with the emotional and psychological upheaval of the dementia. Drama.

12. How important is form to you in this collection?

Form is intrinsic to all matters to me. It goes to voice in the poems, and I hear that as authenticity. Critical to me. The look of the poem is a voice, and how that look works on this page and in conversation with the others creates more voices or blend to make another voice or clashes to make others. The line lengths, even or jagged, the syllables: metered or random-seeming, the rhymes, repetition – all go to content, believability of the story, the dream which I want to be vivid, continuous until I want at the right moment to snap my fingers and bring readers out of it. I don’t work in received form. Free verse is not without rules, however unwritten.

13. In my own experience of my stepmom’s Alzheimer’s her responses bring a sense of the fantastic, the absurd. How does this relate your notion of “chaos”?

The “fantastic, absurd” you mention requires the ordinary, the rational to work to counterpoint. And I hope is within the poems. The “chaos” I refer to also is the conflict between the disease and the person with the disease and the person before they showed symptoms and the family members who remember that person and hold onto them while still “dealing” with that person during the progression of the disease and so the changing relationships are tumultuous. That shows up within the poems and between them, I hope. After, too.

14. The two poems about dance seem to bookend the collection. How intentional was this?

Interesting – I was not conscious of this. I was more aware of movements – of the flux in everything for assorted reasons. But now that you point that out I can see the varying strategies in the changings. Estelle, before the disease was always mercurial – this was her nature as the son understood it, and when the disease started showing up it was not easy for the son to tell if this was one of her games, dances. It was in part – she was aware of something wrong and was covering as she was covering the poor grades for her son. This dance or balancing act is, as I see it, a way of dealing with the world and later her destabilized mental condition until she couldn’t. And in the final poem, that dance is one of balance, too but with a sense of acceptance and perhaps a new perspective, a humor.

15. With phrases like ” there’s no reaching her” and “trying to catch them” there’s a sense of unbridgeable space. How important was it to give this sense of the unattainable?

I think that’s why we write in poetry and not prose – to use language that is inherently inefficient to capture what we believe is essential. We want to see it clearer so we put it down but the sentence and conventions of grammar are the wrong tools to examine it and are surely going to fail us. So, we break the rules with syntax, metaphors, lineation and more – all to reach out and connect with the ineffable, perhaps the unknowable but no, it must be knowable, right? To have your mother not know you, to no longer know her as she was for so long in great part – to long for her, the only one who can give you what she gave you – yes, that was what I was reaching for as she was with me and at the same time, gone.

16. Once they have read your book what do you wish the reader to leave with?

Oh, I don’t know that. Better off asking my poems. On second thought, I hope they see my mom, my dad, my family, and themselves in some of the situations. The pain and the beauty, and something of a connection happens. Maybe I should have stuck with my first answer?

Spaces by Clive Gresswell (erbacce-press)

This is a neatly produced chapbook from erbacce-press which is nicely laid-out and has a cover design incorporating (I think) a photograph of the author which has been adapted into a double-image by Alan Corkish.

There are 21 poems, each titled and each taking up a page. The overall title relates to the layouts of the texts which are split mainly into phrases, single words and occasionally longer pieces, halfway towards sentences, which suggest narrative structures but are fragmented and full of what I can only call texture. For me this is the most interesting of Gresswell’s recent chapbooks as there’s something almost Shakespearean about his use of language, where a variety of dictions interplay and resonate to great effect. There’s certainly a lyrical element to this work but it’s mixed with a dark foreboding quality which talks of ‘our times’ and has a sort of apocalyptic quality throughout. Take…

View original post 322 more words

The Traces: An Essay by Mairead Small Staid (Deep Vellum / A Strange Object)

Mairead Small Staid’s book is the kind of writing the term ‘Creative Non-Fiction’ was invented for. It is a travelogue, a memoir, a romance, critical literary exposition, art history, and a quest, all in one. It meanders, branches, follows its own diversions, conversing amiably with the reader as it reflects on time, memory and place, looking for and considering the nature of that most elusive of human conditions, happiness.

Staid’s book is ostensibly about a period of time spent studying in Florence, her friends there (one, Z, who she lusts after, flirts with and eventually beds), Italian art, architecture and culture, and trips from there to elsewhere in Europe, Venice and Paris included. It is also a commentary on Renaissance painting, and books, especially Italo Calvino’sInvisible Cities, the novel where Marco Polo invents or describes cities that turn out to be variations on Venice itself. Sappho, Anne Carson…

View original post 596 more words

Agri culture by Mike Ferguson (Gazebo Gravy Press)

Before Mike Ferguson became an English teacher (he’s now retired), he tried his hand at farm work, imbued with the back-to-the-land enthusiasm of the 1960s and 70s counterculture. Having emigrated from the USA, Ferguson took a job for three years near Ipswich, and then lived and worked part-time in the Chiltern Hills whilst he studied at Oxford.

Although perhaps the reality of labouring, even within agriculture, hit home, and Ferguson followed his degree by training as a teacher, eventually moving to Devon, and then engaging with the Devon reading and publishing literati, especially in the context of readings, workshops and magazine & booklet production within education, Ferguson still goes slightly dewy-eyed and nostalgic about farming, as evidenced by this beautifully produced, austere pamphlet.

Much of Ferguson’s current writing is process-driven: he uses erasure, pattern, word-shapes,Humument-type explorations and collage to write through and from writing both old and new…

View original post 583 more words