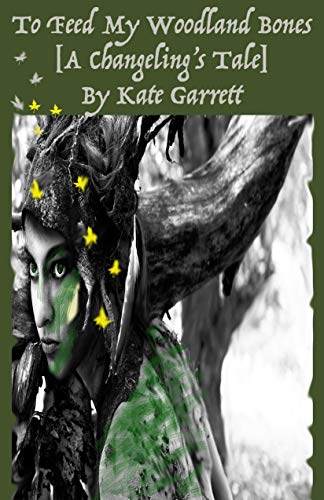

Kate Garrett

is a writer, editor, mama, sometime drummer, and folklore obsessive who often haunts 465-year-old houses (as a history and heritage volunteer). Her work is widely published online and in print, and has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, four times for Best of the Net, and longlisted for a Saboteur Award. She has also performed at events and festivals around the UK since 2011. She is the author of several pamphlets, most recently To Feed My Woodland Bones (Animal Heart Press, 2019), and her first full-length collection The saint of milk and flames was published in 2019 by Rhythm & Bones Press. Her next pamphlet, A View from the Phantasmagoria, will be published by Rhythm & Bones Press in October 2020. Born and raised in rural southern Ohio, Kate moved to England in 1999, where she still lives halfway up a hillside in Sheffield. kategarrettwrites.co.uk

Link to her 2018 interview with The Wombwell Rainbow:

https://thewombwellrainbow.com/2018/10/06/wombwell-rainbow-interviews-kate-garrett/

The Interview

1. How did you come upon the marvellous idea of portraying otherness through elfness?

The first poem I wrote in this sequence was ‘Changeling’ – it came to me years before the others, in about 2012, when I was still working on my BA in creative writing at Sheffield Hallam. I’d been thinking a lot about my childhood for various reasons, and I’d felt like a changeling for a long time by then. People have always said ‘you look like an elf/faery/pixie/etc’ to me and this idea of being switched at birth with an otherworldly creature and being rejected by the human parents really resonated with me for all sorts of reasons: surviving a troubled childhood, being autistic, being queer. In 2018 I wrote ‘An elf in awe of her human lover’ which is a love poem to my husband for accepting everything about me, all of the otherness, inside and out. Then I just ran with the idea of exploring largely unexplored parts of my life through a story of a changeling growing up and slowly becoming more human

1.1. And becoming more human you ask indirectly what makes us human?

Yes, I suppose that’s true. And I think being neurodivergent and an abuse survivor with c-ptsd makes a person think even more about what it means to be human – because people with these kinds of conditions are forever trying to make it all work with our neurological differences and/or our heightened anxieties. There are a lot of things that qualify as human, and it’s certainly not just social niceties and fitting in, but things like love, joy, grief, wonder, anger – all the experiences and emotions that make up our lives. Those are all the important bits, and the changeling discovers these things are what matter the most in her own life.

1.2. Accepting her elfness too? You seem to be saying otherness is always magical.

She’s definitely accepting of herself as she is – the elf side as well as the human side. She finds a way to successfully be both, and she’s much more content with that synthesis. And no, I don’t really think of otherness as being particularly magical, as in, a superpower or something – it’s just different. I think the world of faeries or elves would be something we don’t quite understand, and to us the legends and lore about these beings all certainly seem magical, but to them it would all be very mundane, wouldn’t it? I think it’s about the perspective on what is ‘average’ or ‘normal’ or ‘standard’ – it’s a sliding scale!

2. A stranger in a strange land that gradually becomes familiar. Motherhood is also explored delicately, as seeing children as different from their parents. Growing up as the difference between parent and child becoming more pronounced.

That’s definitely part of it. Throughout my own childhood I was often not treated as an individual, a person with my own thoughts and feelings. As a mother, I have always encouraged my kids to be themselves, think for themselves, have their own interests… it seems to be working out fine. The changeling in the poems becomes a better mother through understanding how difficult it was to be someone’s child.

3. Also hints the idea of an immigrant or refugee finding a home in a foreign land.

That’s also definitely me! I was born in Ohio but moved to the UK at 19, and have been here ever since – over 20 years now. But strangely enough that didn’t really occur to me when I was writing this book. I wish I could say it had, because that also makes sense in some ways – but the cultural change between Ohio and England felt natural and right, where all the other adjusting I’ve done in my life has been more difficult.

4. Your poems don’t rhyme.

Well, they don’t rhyme on the ends of lines (and some are prose poems that don’t have typical “lines” at all)… they do rhyme internally, however, or else they have sound patterns running through them, like half rhymes or alliteration. Sound is a very important aspect of poetry for me, I work with it very deliberately.

4.1. Like a sound sculpture?

That’s a great way of putting it – especially since my writing process usually involves carving something decent out of the initial formless splodge of ideas and words…

5. The title is “To Feed My Woodland Bones”, but you live in a city. Is this a tale of a move from woodland to an urbanised environment?

Well, I live in a city with a lot of trees, but all the same, I haven’t always lived in a city – and certainly didn’t when the events in the poem ‘An elf turns inside out for the dragon’ (where the title line is found) transpired. I grew up in a rural area, and the more pleasant memories from my childhood involve trees and woods – you couldn’t keep me away from them! The title is less about a move from one place to another, and more about a certain type of place being part of who I am (down to my bones, you could say), and that’s true wherever I am.

6. A psychological place.

Sort of. I did mean a type of physical environment – in this case specifically the woodlands, forests, trees, wherever they might be (the British ones of my adult life or the American ones of my childhood) have helped make me who I am. Other natural settings have too – bodies of water, mostly, which comes up in this book and other things I’ve written. But most of us have deep relationships with the landscapes in our lives whether we are aware of it or not, so I guess that translates as psychological, too. And what it represents would depend on the type of environment and what it means to us.

7. Repetition of lines is used to great effect especially in the really positive final poem “Pixie-led”, the line “in the bottom of the glass” as if you are writing poems as spells.

Thank you – ‘Pixie-led’ was definitely supposed to be spell-like, disorienting, and enchanting, because to be ‘pixie led’ is to lose your way on the moors (this legend originates specifically from Dartmoor in the southwest of England, I believe) and of course that’s meant to be confusion caused by faery folk. The last poem is inspired by getting engaged to my now-husband, so again the changeling is disoriented and enchanted by the human – I invert the lore a lot in this way throughout the sequence. And as for poetry as a spell, I do think as an art form it is working a practical sort of magic, whoever the poet is – we have to pull images seemingly out of the air, get the ideas and feelings across in just-so ways. Art is magic and vice versa.