Mick Jenkinson

is a poet, songwriter, musician & freelance arts practitioner from Doncaster. He is a member of a number of community groups whose aims are to increase arts engagement in the Doncaster region and he delivers song writing and poetry writing workshops. He was the director of Doncaster Folk Festival for 5 years and a founder member of the Ted Hughes Project in Hughes’ childhood hometown of Mexborough.

He is founder and MC of Well Spoken, a monthly poetry performance evening held at Doncaster Brewery, and a founder member of the South Yorkshire poetry collective Read 2 Write, a group mentored by Ian Parks. His first pamphlet, A Tale to Tell, was published by Glasshead Press in 2017, followed by When the Waters Rise, published by Calder Valley Poetry in 2019.

His poems have appeared in Pennine Platform, Dream Catcher, Dreich, Setu Mag, The Don and Dearne Collected Poems Vol 1, Black Bough Poetry’s Christmas & Winter Anthology Vol 1, and Christmas & Winter Anthology Vol 2, the exhibition these poets, our kin / these poems, our stories in the Frenchgate Shopping Centre, Doncaster, The Northern Poetry Library’s collaborative online work Poem of the North, and the book Tom’s Territory by Terry Chipp.

In 2017 Mick formed a songwriting partnership with the poet Ian Parks and received an Arts Council commission resulting in the album of songs and poems about their locality, Songs of Our Town. Mick has since released two further favourably reviewed solo albums, When My Ship Puts out to Sea and The Wheel Keeps on Turning. Find him at http://www.mickjenkinson.co.uk

The Interview

Q:1. How did you decide on the order of the poems in Iron Harvest?

There were a few key drivers for the order, but beyond that it evolved pretty organically, and was more to do with the indefinable feel of how it flowed as a reading experience.

Firstly, the opening and closing poems needed to be both strong, and at the same time to make some sort of statement. Although I’d no wish to create a themed collection, it’s undeniable that I write much that’s geographically rooted in some way, and more specifically, about my hometown. Opening with This River seemed quite natural as it’s a manifesto of sorts for my love of Doncaster and its landscapes, and readings have indicated that it connects with audiences very viscerally. At the other end of the book, Past Brodsworth is my most anthologised poem, it’s really been around the block and proved its worth! I see that as a sort of origin story for the town.

The second consideration was to give a flavour of the scope of the collection within the first few pages, so it was important that a variety of styles and subject matter were represented, but without it seeming disjointed.

Then, I specifically did not want the book to feel as if it was in themed sections, so other than a couple of instances where I thought a pair of poems belonged together, I was deliberate in interspersing poems that might be seen to have common subject matter.

There’s also a temptation to cluster the poems one regards as the strongest towards the front, and I did not want it to be like one of those vinyl LP’s where all the singles are on side one and no-one listens to side two! so balance throughout the collection was probably the strongest deciding factor for how it ended up.

Q:2. Why the title “Iron Harvest”?

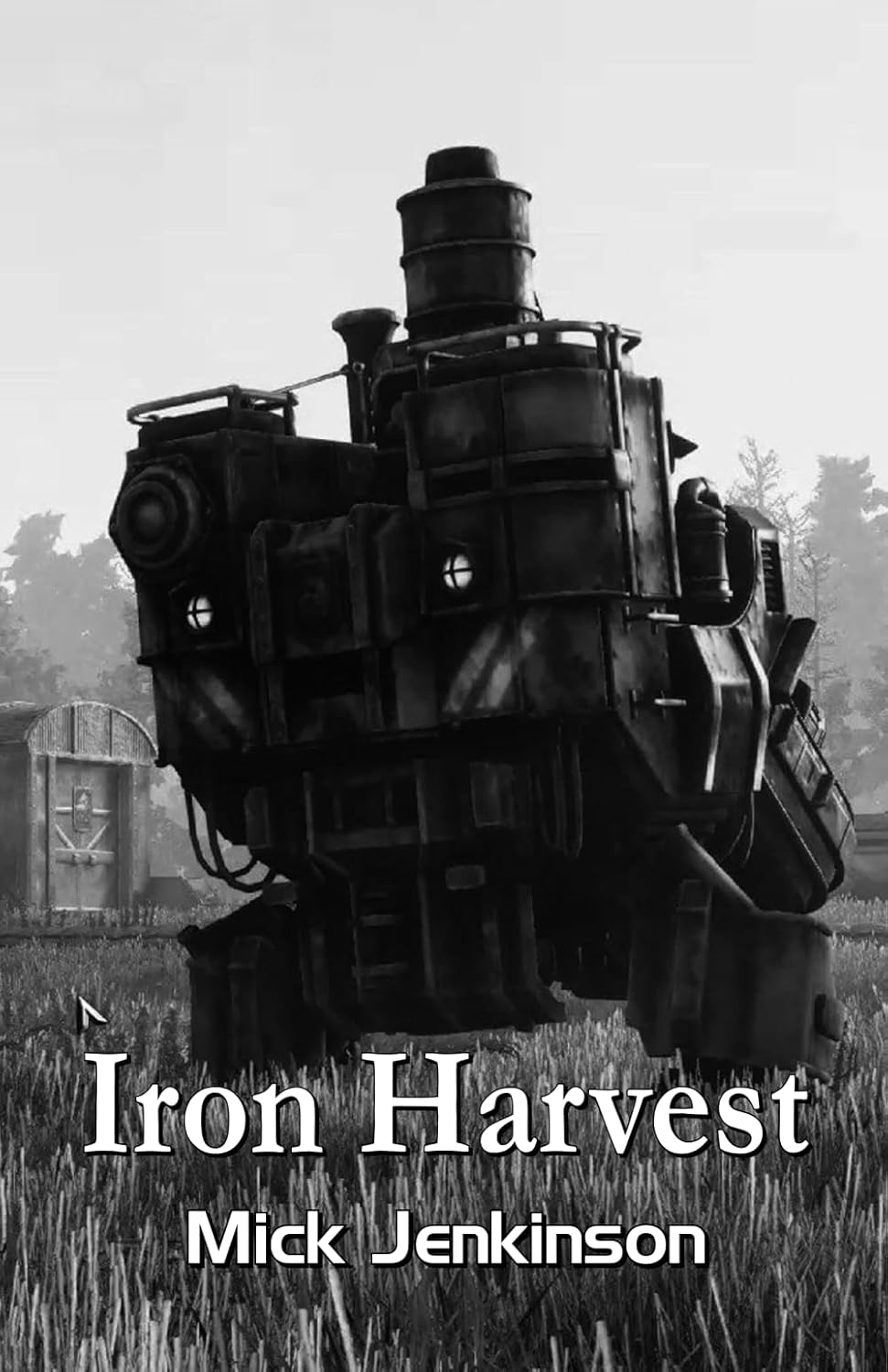

All through the process of getting the material together for the collection, I’d used the working title This River, because I decided early on that would be the opening poem. But when it came to finalising the manuscript, there was a feeling that it was a bit too generic. I had a meeting with Ian Parks, who had really acted as de-facto editor and assisted me on every facet of the book’s production. Over a coffee and a scone at Doncaster Library we tossed around various options for a title that would be more impactful, and Iron Harvest just sort of emerged. As Ian states in his foreword, there’s a metaphor there for the poetic process of bringing to the surface what’s hidden. The icing on the cake was that the publishers, Cyberwit, came up with that beautiful cover image, which manages the difficult trick of being both enigmatic while also capturing the essence of what I was aiming at.

Q:3. How important is poetic form in this collection?

One essential element of convincing poetry, to me, is the matching of form to content, so in that respect I’d say it’s essential. I treat the formal forms of poetry as structures within which to arrange my thoughts, and I like that discipline of the framework being in place as a template or pattern. That said, a poem will usually begin more organically with an assembly of words, and at some point, it will either suggest a formal structure or it won’t. I have very rarely set out to write, for example, a sonnet or villanelle outside a workshop environment, but it gives me a sense of satisfaction when one materialises.

Q:4. How important is nature in your writing?

I suppose a cursory flick through Iron Harvest would answer that nature is

central to my subject matter, just as it is fundamental to my view of the

world. One of the reasons I write at all is to explore and discover what

spirituality means to me, and the natural world offers most to me to make

sense of that. I’ve always been an urban dweller, but easy and regular

access to countryside is essential to the way I live and it’s from those

environments that my poetry seems to arise most frequently. That’s not

deliberate, just the most forceful root of inspiration.Q:5. One poetic form occurs more often in this collection. What attracts

you to the villanelle?I’m not a self-analytical poet, so it’s not easy for me to give a pat

answer. A couple of the first poems that made an impression on me when I was

young, Dylan Thomas’s Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night and Auden’s If I

Could Tell You, were villanelles, and sometimes those early influences can

be the most potent ones. I think there is an elegance both in the way a

villanelle looks on the page and the circular nature of its repeating

structure. We often start with a significant phrase that becomes the key to

a poem, and the villanelle puts that phrase centre stage. The structure

dictates that you have a limited and finite number of stanzas and lines to

make sense of what you want to say, and an obligation to resolve it in some

fashion. I find that discipline very rewarding.Q:6. How has Edward Thomas influenced your poetry?

There are several aspects of Thomas’s poetry that I take as touchstones for

how I would like to be able to write. In no particular order, his insistence

on brevity and economy, the crispness of his language, his use of nature

both in literal descriptions and as a metaphoric tool, and his love of

strict poetic form (allied to the fact that he often ‘invents’ forms) and

how perfectly they reflect his subject matter.Q:7. Once they have read your book what do you wish the reader to leave

with?All the things we hope to get from good art, I suppose. I want to present a

view of the world that is personal and universal, and hope people can relate

and respond to it emotionally. I want people to me moved, interested,

challenged, entertained. Whatever they leave with, I would wish that people

consider it to have been a worthwhile experience.

New collection of poetry for 2025 Iron Harvest available from amzn.eu/d/2J5Xkhm