Kelly Davis

lives in Maryport, on the West Cumbrian coast, and works as a freelance editor. Her poetry has been widely anthologised and published in magazines such as Mslexia, Magma, London Grip and Shooter.In 2021 she came second in the Borderlines Poetry Competition and was longlisted for the Erbacce Press Poetry Competition. She has twice been shortlisted for the Aesthetica Creative Writing Award and she appears in the Best New British and Irish Poets 2019-2021 anthology (Black Spring Press). In 2021, she collaborated with Kerry Darbishire on their poetry pamphlet Glory Days (Hen Run).www.kellydavis.co.uk

The Interview

Q:1. When and why did you start writing poetry?

I always loved poems and rhymes as a child and I was lucky enough to have a father who read me Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur when I was very young. I know I started writing my own poetry in 1972, aged thirteen, because I still have the book in which I painstakingly wrote my first few poems in calligraphic script. Like many teenagers, I mainly used poetry as an outlet for difficult emotions. Expressing grief and anger in words, and particularly in poems, made me feel better – perhaps because it helped me understand my feelings and gain some distance from them.

Q:1.1. What was it about Malory’s poem that stayed with you?

I think the tragic love triangle between Arthur, Guinevere and Lancelot. I was too young to understand it at the time but I somehow sensed the enormity of the betrayal.

Q:2. So you would say this action of your father introduced you to poetry

I think it was less about poetry at that stage and more about the beauty of Malory’s words and the power of the narrative. Many of my poems have a storytelling element so perhaps that early introduction to Malory’s epic somehow fed into my development as a poet.

Q:3. How did you decide on the order of the poems in both of your books?

My first pamphlet, Glory Days (Hen Run, Grey Hen Press, 2021), was a ‘poetic conversation’ with Kerry Darbishire about the stages in a woman’s life, and our relationships with our charismatic mothers. It was relatively simple to arrange the poems, beginning with memories of our teenage years, followed by finding love, then the experience of motherhood, coming to terms with getting older, and thoughts about our own mothers aging. Finally, there were some poems about losing our mothers. Thankfully, my mum is still alive but Kerry wrote very movingly about the things her mother left behind – a house full of memories and the dried flowers she left in her diary.

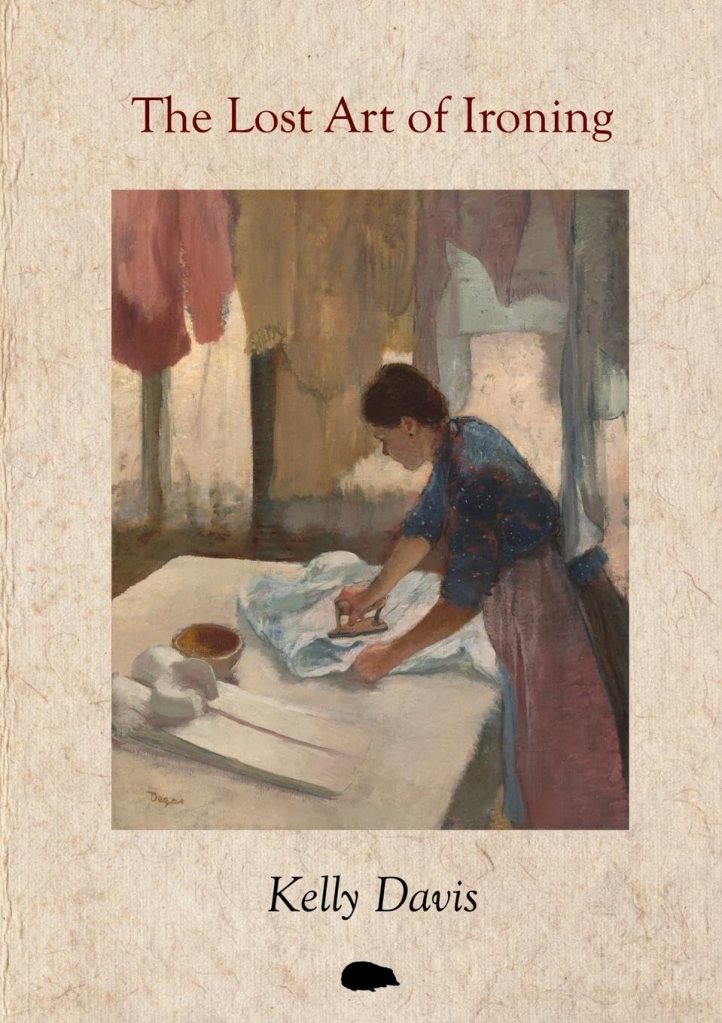

Arranging the poems in The Lost Art of Ironing (Hedgehog Poetry Press) was much trickier. This newly published solo collection has several themes and deals with other women’s lives as well as my own. I always knew I wanted the book to open with ‘To My Hands’, which is really my life story in a single poem and I was originally going to follow it with other poems expanding on particular aspects of my life. However, I sent the draft manuscript to Brian Patten (a long-standing friend and one of my all-time favourite poets). He was kind enough to read it and he thought the poem about Emily Dickinson was one of the strongest and should appear near the front. Once I’d moved that one, I realised that it would be much better to start with other women’s lives and go back to the autobiographical ones later. This arrangement somehow opens the collection out, making it more resonant for a wider audience. In the later part of the book there are certain poems that had to follow each other – for instance, the ones about my Jewish family history. ‘Prove your identity’ hints at later events, mentioning the necklace owned by my great-grandmother which features in the next poem. It also refers to my grandfather leaving Lithuania ‘in time’. This statement is unpacked in the third poem in this little sequence, ‘Trying to Edit the Holocaust’. I wanted to end the book with my modern versions of five Shakespeare sonnets. I love the sonnet form – and the themes of time, mortality and digital technology run through the whole collection – so the book ends with a final rhyming couplet:

‘At last we know that love is what life’s for,

and life is short – so we love even more.’

Q:4. How aware are and were you of the dominating presence of older poets traditional and contemporary?

I suppose the short answer is ‘very aware’. I studied English Literature at St Anne’s College, Oxford, and gained a pretty good knowledge of ‘the canon’, starting with Anglo-Saxon and Chaucer and covering a

range of Elizabethan, Restoration, Victorian and Georgian poets. I was there in the late seventies and the course was still very traditional then, ending with Yeats and Eliot. I had to go to another college to study the American poet Marianne Moore! My favourite women poets were Emily Dickinson and Sylvia Plath

and I loved the Metaphysical poets, particularly Donne, Marvell and Herbert. Outside university, I remember being electrified by seeing Ted Hughes read at a pub in Hampstead; and seeing the Liverpool poets (Roger McGough, Brian Patten and Adrian Henri) made me realise that poetry could break out of the rarefied realm of libraries and lecture halls – and speak to everyone. I love the idea of poets being in conversation with each other across the centuries, and ‘The Lost Art of Ironing’ includes poetic responses to Keats, Eliot, Anne Sexton and Shakespeare.

Q:4.1. What made Emily Dickinson, Sylvia Plath and Donne, Marvell and Herbert your favourites?

In my poem about Emily Dickinson, I explain why I love her poetry:

‘I’d ask her to tell me her secret,

how to distil 200 words into 20,

how to capture a truth

before it slipped away – ‘

It’s also her incredible precision and fearlessness, when writing about huge subjects. I think ‘I heard a fly buzz – when I died’ is one of the best poems ever written about the process of dying.

Sylvia Plath was also fearless and said things no woman poet had said before, smashing taboos and sometimes using shocking language and images, as in ‘Lady Lazarus’. But she could also be tender and lyrical, as in ‘Morning Song’.

With John Donne, I loved the way he used bizarre metaphors, like a pair of compasses or a fly, to talk about love. His brilliant intellect was always at the mercy of his emotions, which gave his poems a sense of tension and struggle. Andrew Marvell created a feast for the senses, in a poem like ‘The Garden’, and also used the power of argument brilliantly in ‘To His Coy Mistress’. George Herbert was the most overtly religious – but, again, his passion came through in poems like ‘Prayer’ and ‘The Collar’.

Q:4.1. What “electrified” you about Ted Hughes reading?

The reading was in a small upstairs room and I was sitting quite close to him, looking up at his craggy face and listening to his deep, powerful voice. He had a very strong presence. At one point he read a poem called ‘February 7th’, about delivering a dead lamb, and the visceral language just floored me. I was left shaking, feeling as if I’d been in front of a firing squad. It was a revelation – that poetry could have such an impact.

4.1.1. How is “the visceral” important in your own poetry?

I want to write poems that deal honestly with the messiness of life – the guts, as well as the head and the heart – so I’ve sometimes written about subjects like sex and menstruation, which used to be seen as

inappropriate in more censorious times. I think poetry can make us more aware of our shared humanity. We all inhabit bodies, and experience the world through our physical senses. Poetry often has an impact on the reader through the shock of recognition.

Q:5. What is your daily writing routine?

I wish I had one! I still work from home as a freelance editor (https://www.kellydavis.co.uk/) and I help run the West Cumbria Refugee Support Network (https://wcrsn.org.uk/) so my poetry writing has to fit in when time allows. Occasionally I experience something that inspires a poem. If that happens I try to get a rough draft typed on my laptop straight away. Then I go back to edit it several times, at intervals. When I no longer feel the urge to make changes, I feel the poem is finished – and ready to share with others. I might road-test it at an open mic – and get feedback from poets I know and respect. I occasionally attend workshops and I have found the January Writing Hour (hosted by Kim Moore and Clare Shaw) a great source of inspiration.

Q:6. How does the natural world feature in your poetry?

I rarely write descriptive nature poems and I certainly wouldn’t call myself a nature poet. Most of my work focuses on human relationships but I’m also interested in the way human beings interact with the natural world. I grew up in London and my husband sometimes teases me about my ignorance of wild flowers, birds, and so on – hence the opening of my poem ‘Cutting Through the Fields’…

‘Today I surprised you / by recognising a yellowhammer’s call’.

In a poem from Glory Days, called ‘Walking in the Languedoc’, the autumnal landscape reflects my feelings as a post-menopausal woman. I liken the vines to ‘aged ballerinas in green tutus’, whose ‘grapes are long gone’. I’m not sure whether that’s personification or pathetic fallacy or both! But it’s my kind of nature poetry.

Q:7. How did you choose the titles for your books?

With ‘Glory Days’, I looked through the manuscript and noticed that my poem ‘Walking in the Languedoc’ ended with two particularly musical and evocative lines:

‘Their grapes are long gone

but the scent of their glory days remains.’

I loved the sound of ‘Glory Days’ and the phrase seemed to reflect our colourful, charismatic mothers, who are celebrated in several of the poems. I suggested to Kerry Darbishire that we should use it as a title for our pamphlet and she agreed. Neither of us realised that Bruce Springsteen had previously written a famous song called ‘Glory Days’! A male poet told me that title had already been ‘taken by the Boss’ but I don’t regret using it for our pamphlet.

For my solo collection, I knew ‘The Lost Art of Ironing’ was a key poem. It mentions women ‘creating order from heaps of chaos’ in the war years, and my mother-in-law using ironing to express her love for her children. As I worked on the book, I realised that my work as an editor featured in some of the poems and I felt that ironing could also be used as a metaphor for editing, in the sense of ‘smoothing’ something that is creased and crumpled. Then, by a stroke of luck, I found the perfect cover image – a painting by Edgar Degas called ‘Woman Ironing’. The title of the collection makes a lot of people smile, as many of us gave up ironing years ago, but it’s also quite poignant, as it makes one think of previous generations – and the losses as well as the gains.

Q:8. How important is poetic form in these collections?

I mainly write free verse, with stanza breaks that correspond to changes in the line of thought or

mood or narrative, but I occasionally use a more traditional form, like a Petrarchan sonnet (‘That Summer’) in Glory Days or the five Shakespearean sonnets at the end of The Lost Art of Ironing. Readers may also spot a couple of prose poems – ‘Snapshot’, which describes a childhood memory, and ‘Meeting in Deep Time’, about editing my husband’s book on Lakeland geology. In the latter poem, the prose form seemed to suit the flowing lava and geological strata I was describing. My new collection also includes a specular (‘mirror’) poem, ‘White Gladioli’, where the second half of the poem reverses the order of the lines in the first half. This poem is about a memory of a tragic accident – and it’s a bit like a film unspooling and rewinding (a metaphor I used overtly in another poem, ‘9th September 1972’). In recent

years, I’ve become more aware of the power of repetition, rhyme and a good line break. To sum up, the content of a poem (thought/emotion/narrative) always takes priority – but I think my best poems are the ones where form and content fit perfectly and reinforce each other.

Q:9. How do the writers you read when you were young influence your work today?

When I was young I read more fiction than poetry. I fell in love with the Narnia books and once spent quite a while in an old wardrobe with my best friend, trying to get to Lantern Waste! After that, books like ‘Lord of the Rings’ and ‘Gormenghast’ sparked my imagination, interspersed with Laura Ingalls Wilder’s tales of pioneer life in America. I was struck by the ability of these authors to paint pictures with words, to take me into other worlds and experiences. I try to do that in some of my poems, whether it’s taking the

reader into someone else’s life (like the woman who sat for Leonardo’s Mona Lisa) or back into one of my own memories (like watching Borg and Nastase play tennis at Wimbledon in 1976). I also loved Shakespeare from a young age – and I think his powerful imagery and use of iambic pentameter have found their way into some of my poetry.

Q:10. Who of today’s writers do you admire the most and why?

I’ve been lucky enough to meet some of the poets I most admire – at readings and workshops. Kim Moore has been a big influence on my writing. I think she goes from strength to strength, in terms of shining a light on the darker aspects of male/female relationships and making every word count in her poems. Her last collection, All the Men I Never Married, has had a big impact – and rightly so. She’s also a very generous mentor. Several poems in The Lost Art of Ironing were first drafted in her workshops. Another, very different, poet I admire is Alison Brackenbury. Her delicate, beautifully structured poems draw on her rural upbringing and family history. I love the way she often uses rhyme sparingly and to great effect. There are really too many wonderful contemporary poets to list – but a couple of others that stand out for me are Imtiaz Dharker (who brilliantly fuses Asian and Celtic culture) and John McCullough, who can be playful, funny, whimsical, touching, shocking and everything in between. John often shares his amazing work on social media and it always stops me in my tracks.

Q:11. How important is a “sense of place” in your writing?

I grew up in London and came to live in Maryport, a small fishing town on the West Cumbrian coast, 35 years ago. I love living by the Solway Firth, looking across to southern Scotland, and I have written several poems about this place. West Cumbria is a ‘poor relation’ of the Lake District, with a lot of poverty and deprivation, but it has its own spare beauty. Glory Days includes a poem called ‘Liminal’, written during the pandemic, which has the following stanza:

‘A place of sand and marram grass,

mauve thistles and natterjack toads.

Flat and calm, with southern Scotland

visible across a silver strip of sea.

A liminal space, reflecting

the limbo we are in.’

Q:12. Why do you write?

I write because I feel the need to express myself creatively and communicate with my fellow human beings. It gives me great joy and satisfaction when a poem falls into place – ‘the best words in the best order’ as Coleridge put it. It’s wonderful when someone tells me that one of my poems

has moved them in some way or resonated with their own experience.

Q:13. Why is family history in your poetry important for you?

I think we are all, to some extent, shaped by our families – for good or ill. I had a very happy upbringing, and I have a particularly close relationship with my mother, but all my family members are aware of our history as members of the Jewish diaspora. If my grandfather hadn’t left Lithuania when he did, he would have perished in the Holocaust, and none of us would exist. That is quite a salutary thought. My family also suffered a tragic loss on a family holiday in 1972, when my three-year-old sister drowned. It took me a long time to write about these very painful events but I think the poems dealing with them are among the most powerful ones I’ve written. When people come up to me after readings, those are the poems they often want to ask me about. Sometimes poems about grief and loss can be strangely healing.

Q:14. How did you collaborate with Kerry on “Glory Days’

It was a very easy, joyful collaboration. We already knew each other through workshops and poetry residentials in Cumbria – and we saw that Mark Davidson at Hedgehog Poetry was running a competition for ‘poetry conversation’ pamphlets. It turned out that we both had quite a few poems about our mothers and about the stages in a woman’s life – and I was delighted when Kerry invited me to collaborate with her. We started sending each other poems and they seemed to fit together very naturally. In the end, our pamphlet ‘Glory Days’ wasn’t selected for that competition but we both really liked it and wanted to find another home for it. Kerry showed the ms to Joy Howard at Grey Hen Press, who specialises in poetry by women over sixty. Fortunately, Joy liked it and agreed to publish it under her Hen Run imprint. She helped us arrive at the final order, gave us a few edits on individual poems, and published it in 2021. Kerry and I did several readings together (both in person and online) and I think audience members enjoyed the fact that we had different voices and styles but similar concerns as women poets, and the book really was ‘a poetic conversation’.

Q:15. What literary projects are you on with at the moment?

I have a pamphlet of poems about my father, which I’ve submitted to a few competitions. I also recently sent in an illustrated pamphlet about insects, animals and birds; and Kerry and I have been working on another collaborative pamphlet about food, cooking and kitchen implements. Meanwhile, I’m still working as a freelance editor. I mainly work on memoirs these days, but someone has just asked me to edit a poetry collection and I’m looking forward to doing that.

Q:16. Once they have read your book what do you hope the reader will leave with?

I hope some of the poems will stay with readers – because they find them particularly moving or insightful or they echo their own feelings or experiences in some way. There are some funny and uplifting poems, between the harder-hitting ones, which should make the collection enjoyable. There are also certain themes, such as the role of digital technology in our lives and the way the Internet has changed our relationship with time, memory and mortality, which I hope will lead people to think more about these subjects. More than anything, I would like readers to feel that they have been on a journey with me – and that the journey has been worthwhile.

Thanks again for spending time interviewing me about my poetry, Paul. Your website is a very valuable resource for anyone with an interest in contemporary poetry and I feel honoured to be included alongside many poets I admire a great deal.