Jacqueline Saphra

is T.S. Eliot Prize nominated, award-winning poet, a playwright, editor, agitator, teacher and organiser. She is the author of ten stage plays, four chapbooks and five collections. Jacqueline is a keen performer and collaborator, working with composers, musicians, visual artists and other poets. She offers mentoring and teaches poetry in all kinds of settings including The Arvon Foundation and The Poetry School.

Her fifth collection Velvel’s Violin is out from Nine Arches Press.

The Interview

Q:1. How did you decide on the order of the poems in your book ?

Just like an individual poem, a book goes through many formal changes in its development. Once I had a critical mass of poems ready for the book, I laid them out on the floor and tried to make some kind of sense of them. I put them together as a single document with no breaks, looking for poems that juxtaposed, connected and bounced off one another and (unusually) shared the manuscript with my husband. It quickly became apparent to both of us that there was too much complexity in this book and somehow it needed more space. I came up with the idea of using, as headings, excerpts some of the poems I’d been reading over the previous few years that had been influential on the book. This helped me to give the sections a kind of cohesion. I tried several different groupings and once I’d arrived at something I thought was workable, I drafted in my daughter Tamar, who is, handily, a dramaturg and theatre director and has an understanding of structure and narrative. She helped me take some poems out, add some poems I’d dismissed, and make sense of the sections. Of course sections are interesting in a poetry book, because the content of many poems can cross over from one section into another. So this became an endlessly reiterated and painstaking process of shifting poems around until they found their positions. Eventually, after editorial meetings and correspondence over a period of months with Jane Commane, my editor, the book reached a point where moving any one poem to another place had a disruptive ripple effect on all the others and upset the balance. That was how I knew the book was done. Although there was a very, very late change in the final manuscript when I suddenly realised the final two poems needed to be swapped around. That was a surprise! The same kind of surprise, in fact, that you sometimes get when writing an individual poem.

Q:2. How was the book shaped by current as well as past war and conflict?

I have always liked historical narratives because however terrible the stories might be, they are over! Notwithstanding, I had always intended and understood from the early days of writing this collection, that the past and present constantly bleed into each other and we fail repeatedly to learn from past conflicts. Just as I was building momentum in the writing of the book,, the Russian invasion of Ukraine really sharpened and focused this view. It became impossible to carry on working on ‘Velvel’s Violin’ without letting the new, devastating war in Europe become part of it. Our current geo-political disturbances, ongoing wars in many different countries and our so-called ‘migrant crisis’ are also a big presence. My own relatives were murdered in concentration camps because they were not given sanctuary in other countries; there are so many parallels with our current moment. You’ll notice that ‘Prologue’, the first poem in the book, is focused on a profound sense of temporal dislocation. During the writing process, in my dreams, my nightmares, my work and my life, I was longer located in either past or present. Time became confusing, fluid and endlessly malleable.

Q:3. How important is music in your collection?

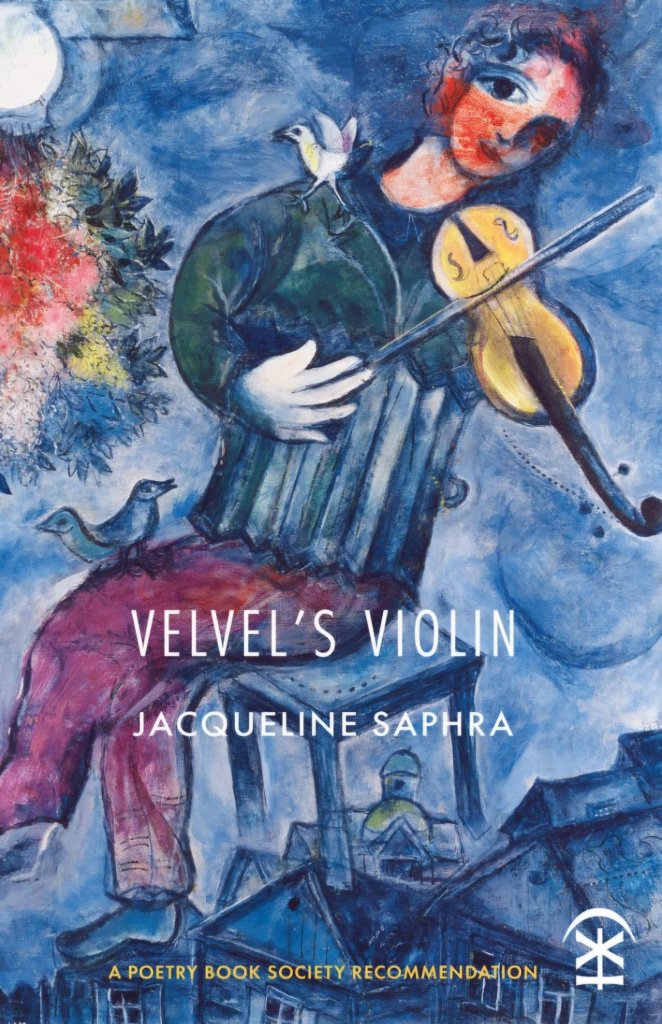

Well, it is called ‘Velvel’s Violin’, and there is a painting by Marc Chagall, the ‘Violiniste Vert’ from 1947 on on the cover. The title poem, is about a violin that was buried at the start of World War Two and never recovered by its owner, who was murdered by the Nazis. I’m a big fan of Sholem Aleichem, the Yiddish short story writer and playwright, who wrote some unforgettable short stories set in the Eastern European shtetls (Jewish villages) in the early part of the nineteenth century. In fact his stories of Tevye the Dairyman, unsparing in the way that they describe the grinding poverty of the everyday lives of most Jews, were the inspiration for the somewhat sanitised musical‘ Fiddler on the Roof’ (which I’ve always loved). The title of the musical was probably inspired by Chagall’s paintings of violinists. Jews in The Pale of Settlement were forbidden to take up most professions but they were allowed to become musicians – and Jewish musicians, unlike most Jews, were permitted to travel. The lucky ones (often from Odessa), if talented enough, could make a good living as violinists and of course the instrument is small and portable. I myself learned the violin as a child and as you’ll see from the poem ‘Peace be Upon You’, I wasn’t great at it, but it felt meaningful and connective in some way. Klezmer music and the mournful sound of classical violin definitely formed the soundtrack in my consciousness while I was writing the book. A long time after writing it, I understood that the burial of the violin in the title poem represents to me the many buried victims, and all those voices that were silenced by the Nazis and their collaborators.

Q:4. What is the significance of poetic form in the collection?

There are some given forms in the book – but mostly I didn’t find even the sonnet, my go-to form for dealing with hot subject matter, particularly helpful. It was as if the constraints of form couldn’t hold the immensity of the material. The poems needed their own forms and often spilled over in unexpected ways.

Q:4.1. How did it spill “over in unexpected ways.”?

‘Remains: Berlin 1945’ is a poem based on the end of the second volume of Volker Ullrich’s biography, ‘Hitler: the Descent’ was so filled with horror it took many drafts for it to find the scattered and uneven form.

‘1939’ was a piece I couldn’t corral into a poem shape – although I tried – and became a kind of hybrid form, what I often describe as a proem: something with the distilled quality of a poem but the appearance of prose.

“Going to Bed with Hitler’ became little squares of prose poems coming one after the other – again, a way of making sense of the senseless.

Q:5. How important is food in your book?

I’d say food is and has always been a big part of Jewish life. Useful as a cultural marker for both the observant and the unobservant. We always celebrate with food (or fast) and food has vast symbolic meaning – bread, wine and the seder plate with its metaphorically laden items: the egg, the matzo (unleavened bread), the charoset (mortar for slaves to build the pyramids). ‘Yom Kippur’ is of course all about fasting and how it concentrates the mind, and ’The Trains, Again’ explores the Sephardi (as opposed to Ashkenazi) traditional foods and their place in family life. So I’d say food is not a major component in the book but there is a nod to it in various places as being significant.

Q:6. Travel, especially by train is a running theme throughout. How deliberate was this?

The trains were not a motif I particularly thought of before I wrote the book, but trains of course exist in Jewish history as very significant, especially in relation to the Holocaust so I am not surprised they keep coming up. They exist both in literal, historical terms and also in the subconscious as mostly taking Jewish people to concentration camps and death, but also as a means to escape. When I wrote ’The Trains Again’ I was recalling a friend and I discussing the almost unbelievable sight of refugees being carried into Berlin to safety rather than out of Berlin towards annihilation. I was surprised how often trains appeared and thought of using that motif in the title although the violin won out in the end.

Q:7. Once they have read your book, what do you hope the reader will leave with?

This is a difficult question to answer as I wouldn’t presume to assume or know or even hope. The poem is always in the eye of the of the beholder. But I suppose I can allow myself to dream that the reader will come away feeling galvanised to make a better, more just and peaceful world and to take some responsibility for being a part of that. As Rabbi Tarfon put it – millennia ago – in the epigraph at the start of the collection ‘You are not obligated to finish the work, but neither are you free to abandon it.’

Jacqueline’s fifth collection Velvel’s Violin is out from Nine Arches Press.