Karen Pierce Gonzalez

Bios and Links

Karen Pierce Gonzalez

is an award-winning writer and artist. She lives in the North San Francisco Bay Area.

Karen Pierce Gonzalez

Bios and Links

Karen Pierce Gonzalez

is an award-winning writer and artist. She lives in the North San Francisco Bay Area.

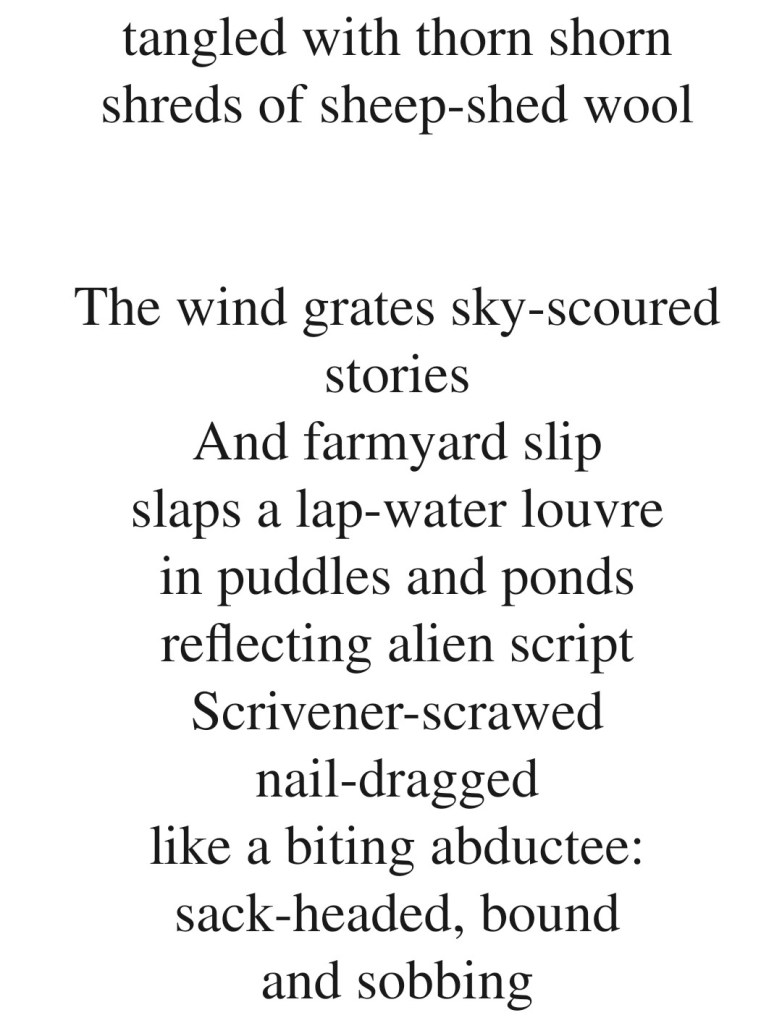

Paul Brookes

Alex Oliver

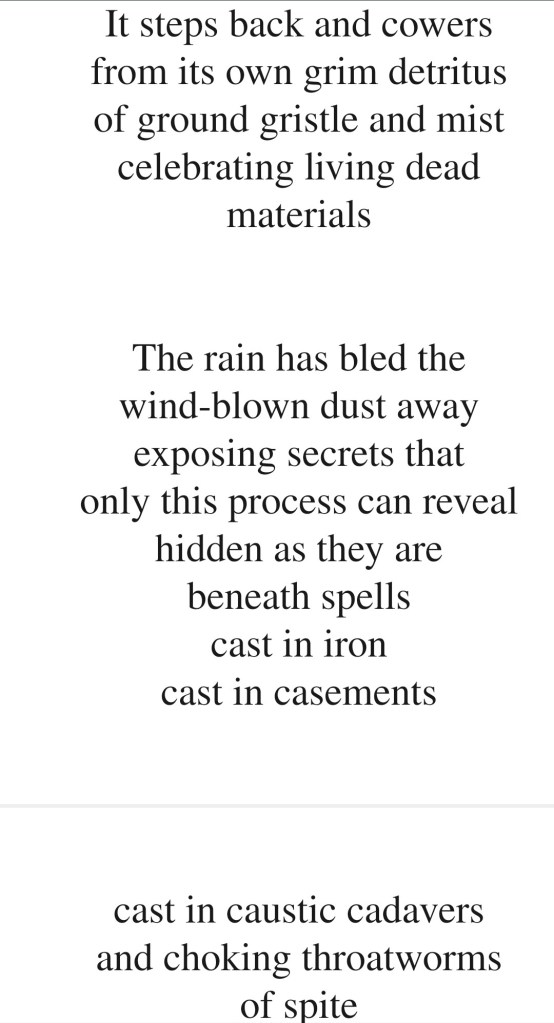

Alan Roderick

He says of this poem:

My book AFTER YOU’D GONE is mainly composed of poems written after the death of my wife BOŽENA to LESLEY JAMES. (Božena died of lymphoma in the late hours of Christmas Eve at the Royal Gwent Hospital in Newport.)

Annest Gwilym

Bios and Links

Annest Gwilym

Pratibha Castle

Bio and Links

Pratibha Castle,

an Irish born poet, lives in West Sussex. Widely published in journals and anthologies including Agenda, International Times, IS&T, One Hand Clapping, Spelt, Tears In The Fence, London Grip, High Window and Stand, she has been longlisted and given special mention in numerous competitions including Indigo Press, Repton, King Lear, Bray Festival, Binsted Arts, Gloucester Poetry Society and Welsh Poetry Competitions. The title poem in her latest pamphlet Miniskirts in The Waste Land (Hedgehog Press), a Poetry Book Society winter selection 2023, was shortlisted in the Bridport Prize. Set in late 60s/early ‘70s Notting Hill and India, this is ‘poetry to reach out and touch, taste, savour’ (Dawn Gorman). Her debut pamphlet A Triptych of Birds & A Few Loose Feathers was a joint winner in Hedgehog Press Nicely Folded Paper competition 2019. Join her at various live and online poetry events in the new year. Signed books and details of guest readings, live and on zoom events, available from

https://www.pratibhacastlepoetry

@pratibhacastle

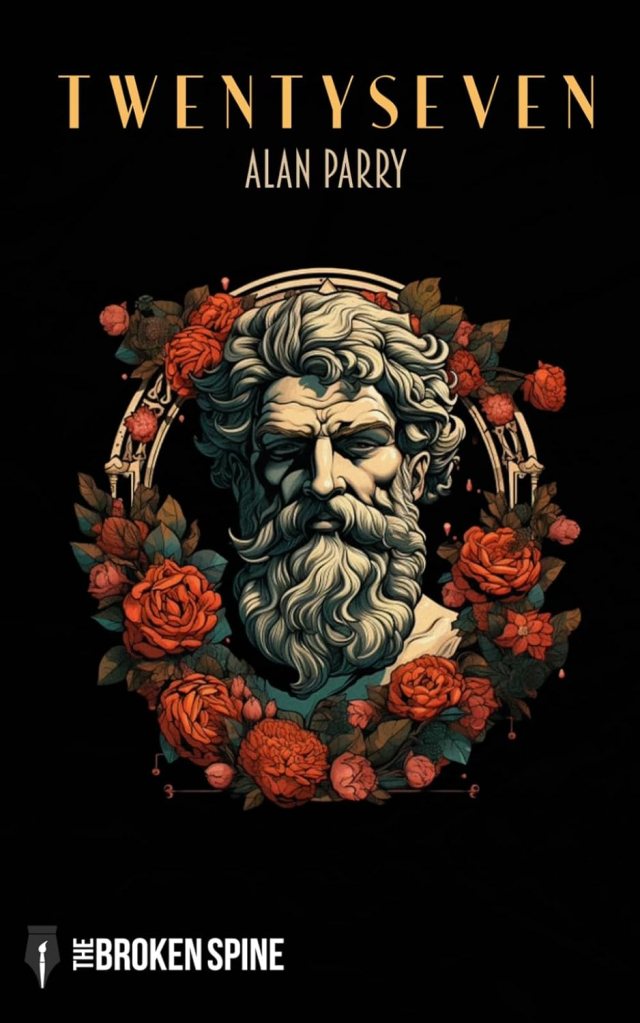

Alan Parry

Bio and Links

Alan Parry

is an acclaimed UK-based poet and Editor-in-Chief of The Broken Spine. His works have been featured by Ghost City Press, Anti-Heroin Chic, Black Bough Poetry, and Porridge. In 2020, he published Neon Ghosts, followed by the award-winning Belisama with The Southport Poets in 2021. His recent works include Echoes in 2022 and Twenty Seven in December 2023. Alan’s one-man show Noir was a highlight at the Morecambe Fringe Festival, showcasing his dynamic range in literary arts.

Alan Parry

is an acclaimed UK-based poet and Editor-in-Chief of The Broken Spine. His works have been featured by Ghost City Press, Anti-Heroin Chic, Black Bough Poetry, and Porridge. In 2020, he published Neon Ghosts, followed by the award-winning Belisama with The Southport Poets in 2021. His recent works include Echoes in 2022 and Twenty Seven in December 2023. Alan’s one-man show Noir was a highlight at the Morecambe Fringe Festival, showcasing his dynamic range in literary arts.

Here’s where to buy Alan’s new book:

The Interview

1. How did you decide on the order of the poems in 27 ?

The journey within the book is far from linear; it’s much more cyclical, like life itself. After the formative experiences of childhood, there’s this escalating sense of excess. It’s like we’re hurtling down a path without brakes, and then After the Rapture comes in. It serves as this moment of clarity, almost a reality check. You’re nudged into pondering the deeper aspects of life, into maturity, introspection, and even regret.

But just when you think you’ve turned a new leaf, Relapse pulls you back in, reminding you that we’re all human and ever-so-susceptible to our primal urges. This chaotic journey eventually leads to a state of spiritual awareness. These final poems echo the end-of-life reflections, touching on what could be greater than just our human experience. It’s like coming full circle but with a newfound wisdom.

I want the reader to not just observe but feel this rollercoaster, to resonate with the highs and lows, and come out of it pondering the bigger questions. So, it’s definitely more than a collection of poems—it’s a life encapsulated in verse.

2. How important is form in this collection?

Form? In this collection, it’s important precisely because it’s not there. The absence of form is integral to the experience I want to create. Look, I’m writing in response to Jim Morrison; it’s got to have chaos, it’s got to push boundaries. You can’t put that spirit in a box. Surprises and shocks are part of the landscape here. So, in a way, the absence of form becomes its own form, reflecting the tumultuous, unpredictable journey I’m taking the reader on. The very lack of structure is what gives the collection its structure, if that makes any sense. It’s all a part of the vibe I’m aiming for.

3. What role does the natural world play in your Morrison poems?

In my Morrison-inspired poems, the role of the natural world is more complex than it might initially appear. Although the core focus is on the human condition and experiences, elements like the indigo deserts in Border Lands act as more than mere setting; they deepen the emotional resonance of the work.

This nuanced relationship with nature is evident throughout. For instance, the red-shouldered hawks in After the Rapture and the bend of birds on the wind in My Mother are part of the thematic and atmospheric fabric of each poem. The sky is another recurring element that speaks to the transient nature of the poems, and of Morrison himself.

Adding further dimensions are the images of rocks tearing holes in the sun and the colour and chaos and Cleopatra skies… This is how I paint. This, at least I hope this, resembles brushstrokes that contribute to a larger portrait. So, while the natural world might not command the spotlight, its presence forms a rich, atmospheric backdrop that, I hope, complements and elevates the human drama.

4. How important is the sense of place in the poems?

In Twenty Seven, I intentionally navigate between Jim Morrison’s ethereal outsider viewpoint and the textured intricacies of domestic human life. This duality serves to take the reader from expansive landscapes captured in lines like ‘indigo sands’ in Border Towns to the intimate spaces of home, as evident in Romance Never Far Behind where a ‘single bar of the gas fire splutters.’

This shift is a calculated endeavor to guide the reader through the multifaceted complexities of both individual experience and universal human emotion. From ‘walking beaches by night’ in Pain Sings Like the Hope of Youth to the cozy, domestic scenes I often depict, my work pulls from a palette that includes both Morrison’s viewpoint and everyday life.

It’s not a coincidence that my poems fling you from beaches, deserts, and expansive skies into bedrooms, bathrooms, and lounges. These shifts are my way of exploring place.

5. What is the significance of the colours in the Morrison poems?

In my collection, Twenty Seven, I’ve wielded colour as a narrative tool that serves as a lightning rod for the reader’s comprehension. Take for instance the ‘sanguine highways’ of Border Towns. It isn’t merely poetic ornamentation but an invitation for a deeper engagement. This is rooted in Morrison’s experience.

The application of colour is consistently utilised to bring both characters and scenes into vivid focus. In Pain Sings Like the Hope of Youth, the juxtaposition of ‘fields of fizzing flares’ with ‘iron smoke skies’ crafts a tableau, that I believe, vibrates with tension and life.

Now, consider the phrase ‘pinto light’ in Night-Time. The very term ‘pinto’ immediately renders the scene patchy, imbuing ‘fleshy shadows & a slide of curves’ with palpable texture and dimension. Similarly, Romance Never Far Behind conjures an intimate scene with its ‘fire-red cigarette tip’ and ‘skin, pale as parchment’ offering readers narrative shortcuts that instantly locate them within the moment.

But it’s not just about the presence of colour; its absence speaks volumes too. Women on the Edge presents readers with a ‘svelte starless sky,’ a sky not just empty but oppressively so. Here, the lack of stars serves as a metaphor for the systemic void of opportunities and freedoms available to women, rendering the sky not just a celestial body but a heavy, suffocating dome, burdened by societal norms and expectations.

So, you see, my choices around colour are not random indulgences. They function as scaffolding, inviting readers into a more nuanced relationship with the text. In this way, like an artist layering paint onto a canvas, I employ colour to bring into focus the scenes and characters that populate Twenty Seven, encouraging readers to delve deeper. What is life without colour and music?

6. How hard was it to not go beyond the idea of twenty seven poems, one for each year of Morrison’s life?

Creating Twenty Seven, a collection featuring one poem for each year of Jim Morrison’s life, was a journey that began in response to Black Bough Poetry’s call for Morrison-inspired works. This initial call served as a catalyst for me. With a personal history deeply intertwined with Morrison—I have a half-sleeve of tattoos inspired by him and a lifelong appreciation for his music and writing—I quickly penned a raft of ten poems. This initial outpouring provided me with the framework and the momentum I needed to complete the collection.

Creative control was paramount to me, and The Broken Spine offered the perfect platform for that. Once the idea took root and those early poems were written, it felt like an unwritten contract; a pact to produce this gift, this tribute steeped in both homage and critique. While the poems might borrow some of Morrison’s imagery and stylistic choices, they are not strictly ekphrastic. I’ve created my own characters, incorporated my own layers of narrative and meaning. I’ve also not shied away from offering a more nuanced, sometimes unflattering, portrait of Morrison, painting him in hues that go beyond mere idolisation.

The idea of limiting the collection to twenty-seven poems, mirroring the years of Morrison’s life, felt intuitively right from the onset. These are brief, concentrated pieces, packed with imagery and emotion, much like the man who inspired them. They are designed to be short and full, echoing the brevity and intensity of Morrison’s own life. Some were even crafted with an eye towards performance, inspired by the likes of Kerouac and Steve Allen, envisioning them accompanied by music. While some poems were written and later dismissed, others, rich in imagery, were adapted from my show Noir but were always destined for this collection.

It wasn’t a question of difficulty in confining the collection to twenty-seven poems; it was more about the clarity that this framework provided. Each poem serves as a tessera in a mosaic, capturing a fragment of a life lived intensely, yet all too briefly. And within that constraint, I found not limitation but liberation, the freedom to explore, critique, and celebrate Jim Morrison in a manner that felt both respectful and revelatory.

6.1. Why revelatory?

The term “revelatory” perfectly captures my approach to portraying Jim Morrison and men who tread the same hedonistic path. Rather than lionising these figures, I strive to present a more honest, nuanced picture. By not shying away from the darker aspects, particularly in how they treat women, I challenge the one-dimensional hero-worship they often receive. This not only enriches our understanding of such complex individuals but also invites a broader societal conversation.

My work examines the allure and the inherent dangers of hedonistic lifestyles. Through this lens, the cyclical nature of excess, self-realisation, and inevitable relapse becomes clear. While my characters manage to attain a degree of maturity, Morrison never did, to his detriment. This critical approach allows for a fresh way to read and understand Morrison’s life and work, questioning societal norms and attitudes that often go unchallenged.

I find the framework of these everyday scenarios crucial. It makes the reader question the outcomes of such excess, both on an individual level and within the larger societal context. By doing so, I believe I’ve introduced a necessary and revelatory layer to the discourse, fostering a more authentic and complex understanding of these individuals and the society that shapes them.

6.2. How do you use Imagistic poetry to “challenge the one-dimensional hero-worship”?

My use of Imagistic poetry in this collection is both a stylistic choice and a tool for deepening the narrative. Much like the Imagists of the early 20th century, who were inspired by the haiku’s ability to capture a moment’s emotional and intellectual essence, I employ this style to amplify the realism and emotional power of the collection. The brevity and starkness of the images serve as a mirror to the complexities of Jim Morrison and the human condition, stripping away the embellishments often tied to hero-worship.

For instance, when I describe “rocks tearing holes in the sun,” it’s not just a poetic flourish; it’s a way of expressing the dissonance between Morrison’s public persona and his inner struggles. Rocks—symbolizing the gritty, unvarnished realities—create gaps in the blinding brilliance of the ‘sun’ that is Morrison’s public image. In doing so, the poem challenges the monolithic perception of him, giving room for complexities to emerge.

Furthermore, the Imagistic style allows for immediacy and engagement. A “svelte starless sky,” for example, can evoke a certain emotional resonance immediately. The reader doesn’t have to read through dense language to grasp the weightiness of the moment; it’s presented in a snapshot, begging them to dig deeper. I hope that this conciseness pulls the reader into a conversation about what’s happening behind the curtain of fame and the complexities that heroes often hide.

In the world of hero-worship, where icons are often flattened into one-dimensional caricatures, the vivid, emotionally charged snapshots created through Imagistic poetry invite the reader to pause, reflect, and engage with the multi-faceted truths. This, I hope, leads to a richer, more nuanced understanding of Morrison and people like him, encouraging a more critical, democratic discourse around our cultural icons.

6.3. I notice you seem to have avoided using imagery from The Doors songs, also Morrison’s own poetry. How deliberate was this?

It’s not entirely accurate to say that imagery from The Doors or Jim Morrison’s poetry is completely avoided. For instance, Moon, or After Moonlight Drive, in my collection is a direct response to Morrison’s song Moonlight Drive. We also share thematic threads, such as references to the same birds of prey which I call red-shouldered hawks.

However, it was a deliberate choice to make sure Twenty Seven was not overly ekphrastic or derivative of Morrison’s work. I wanted the collection to stand alone as an individual expression, something that could be appreciated in its own right while also serving as a nuanced homage to Morrison. I aimed for the collection to be more of a gift to Morrison, rather than a reaction to his artistry.

7. How important is the idea and form of song and music in this gift to Morrison?

In crafting this, I’ve intentionally woven musicality into the work. It’s there in the surprises, in the phrasing, and perhaps most importantly, in the intentional white space between the words. I’ve eschewed traditional rhythms dictated by meter and rhyme to embrace a more fluid, organic musicality. I suppose it’s a nod to the great jazz improvisations as much as it is Morrison himself.

8. How did you achieve the mind altering imagery in 27?

Well, thank you. I’m deeply appreciative of your recognition of the powerful imagery in Twenty Seven. I began by immersing myself in Morrison’s work and other atmospheric pieces, absorbing and reinterpreting motifs from his creations. This process was about crafting an echo of Morrison, yet ensuring it stood as distinctly mine, not derivative.

Amongst the collection are pieces that originated as list poems, which were initially just sporadic notes in my notebook. When I revisited these notes and identified their thematic links, the real transformation started. I polished and experimented with these lines and gradually uncovered the potential they held.

However, the true depth of connection to Morrison’s spirit emerged when I started performing these pieces. With a fear of sounding like a dick here, I felt as though I was channeling something of Morrison himself. Reciting these poems became an act of embodying him, bringing to life a part of his aura and energy. I’m not Jim, nor would I want to be. But I wanted the work to be for him and the performance helped so much. This wasn’t just about delivering words; it was an invocation of Morrison’s emotional and artistic landscape.

9. How did you come up with the stunning front cover image?

The front cover image for Twenty Seven pays homage to Jim Morrison’s fascination with ancient history, spirituality, and culture, combined with his experience of Americana. I imagined creating two metaphorical vases representing these aspects of Morrison’s life. These vases were then symbolically smashed and reassembled into a mosaic, a visual representation of the collision and fusion of these diverse influences. This design captures the complexity and multifaceted nature of Morrison’s legacy, symbolising his impact in a singular, compelling image.

10. How does the quote from Jim Morrison at the beginning of the book, relate to your own aims in poetry writing?

Jim Morrison’s quote at the start of Twenty Seven really opened up a new way for me to approach my writing. It’s like it gave me permission to explore and write in a style that I might not have tried before. This quote kind of unlocked a door for me, letting me step into new areas with my poetry.

A lot of what I write about is the male perspective and masculinity, and these topics can sometimes be tough or uncomfortable to address. But with Morrison’s view of finding freedom in chaos and disorder, I found a different way to look at these themes. It allowed me to be more adventurous and critical in my exploration of these subjects.

The quote from Morrison wasn’t just an intro to the book; it was a key that let me explore deeper and more complex aspects of life in a new light. It’s still about being critical and thoughtful, but now I’m doing it with a fresh perspective that Morrison inspired.

11. Having read 27, what do you hope the reader will leave with?

With Twenty Seven, I really hope readers will get a good grasp of what I’m about as a poet. I’d love for them to enjoy this collection enough to explore more of my work, like Neon Ghosts where I dive into American culture and memories, or Echoes, which is a more personal look at my own life. I want to spark their interest and get them talking about and sharing my poems.

It’s also important to me that readers see my skills as an editor. I hope they’ll notice the care and attention I put into Twenty Seven and feel confident in trusting me with their own writing.

On a deeper level, I want readers to connect with my poems, to see parts of their own lives and feelings reflected in my work. It’s about making a real emotional connection.

And lastly, I want to keep the memory and greatness of Jim Morrison and The Doors alive. This collection is both a tribute to Morrison and a way to keep his legacy going, showing both his amazing talent and his human side.

Overall, my goal is for Twenty Seven to resonate with readers on many levels, whether it’s through enjoying the poetry, seeing a bit of themselves in the work, or keeping the spirit of Morrison’s music alive.