-Louise Longson

cleared enough space in her spare room and head to start writing ‘properly’ during lockdown 2020. She is published by One Hand Clapping, Fly on the Wall, Nymphs, Ekphrastic Review, Obsessed with Pipework, Indigo Dreams Publishing, The Poetry Shed and others. She is a winner of Dreich’s chapbook competition 2021 with Hanging Fire. A qualified psychotherapist, she works with historic trauma and the physical and emotional distresses caused by chronic loneliness. Lives with an orange cat and a silver Yorkshireman. In her head, sky is always blue, grass always green, leaves always golden. Needs to get out more.

Twitter @LouisePoetical

The Interview

1. When and why did you start writing poetry?

I started in a desultory fashion some years ago. Mostly I wrote light-hearted verse, usually just to enter local competitions. I met Deborah Alma (the Emergency Poet and founder of The Poetry Pharmacy in Bishop’s Castle in Shropshire) in about 2014. She came and did a couple of events for a mental health project I was heading, and I was reminded of the impact of poetry on people’s well-being and how using it as a form of expression is so powerful. So, I started to write a bit, but never seemed to find the time to do it in a committed way – easily distracted and not very disciplined. I don;t think I know how to be, really. Lockdown in 2020 was when it really started properly. I have an anxiety issue and, before lockdown, had taken enormous strides to overcome it. I was generally fine at work, on public transport (I don’t drive), in restaurants and pubs – all sorts of places – after years and years of not being fine, and spending a lot of energy keeping the anxiety at bay. While exhausting sometimes, positive change was happening. The not-driving meant I spent a long time journeying to and from work on trains and buses – crowded ones where you have to stand up, so writing while travelling didn’t really work for me, and keeping the anxiety under control was often my main focus. Lockdown meant I had both time and the headspace to do something else. I remember reading about people who had started learning Japanese, making sourdough bread, playing the saxophone – all that sort of thing – and thought about poetry again. I did a couple of online courses with Future Learn and the WEA, but I knew I would need some other guidance, otherwise I’d just find an(other) excuse not to sit down and write. I looked around at online courses, but it’s so hard to know what’s any good or not. So, I asked Deborah, who recommended Wendy Pratt to me. Wendy does a number of brilliant online prompt-a-day courses and workshops. They really helped – providing great prompts, having a group of peers to support and offer constructive criticism and reading what others produced is amazing. From there, I asked Wendy to mentor me for three months, and that was the real ‘game-changer’. She gave me a really good understanding of the process of writing and editing and – importantly – submitting work. I don’t think I ever would have done it without her encouragement. I’ve kept writing and submitting ever since. I aim to write something every day. And I generally do, even if it’s not great, it’s something. Even a few notes, words, an idea – that’ll do!

And I think the ‘why’ is that, for me, it’s almost a form of therapy. I work with people who are experiencing mental and emotional health issues that stem from their loneliness and isolation, which stem from trauma and long-term mental or physical health conditions. Along with my personal experiences, this sort of thing forms the subject matter of a lot of my poems. So poetry in a way is a process whereby I try to make sense of the world and get stuff out of my head, look at it, and manage it. I’m interested in myth, folk-tales, religion, song – other ways of making sense of the world – and nature is a source of wonder, solace and sometimes fear. So it all combines toward the poems and a sort of healing process.

2. Who introduced you to poetry?

I think my mother. We didn’t have many books at home, but did have those ‘Books of Knowledge’ kind of things that were a compendium of all sorts of stuff and then some encyclopaedias. I remember a poem in one of them called ‘Lochinvar’ by Sir Walter Scott (and it had a terrific picture of a chap in a kilt brandishing a broadsword next to it), and also being given ‘A Child’s Garden of Verses’ by Robert Louis Stevenson for a birthday present quite early on. I was an early and avid reader, and spent a lot of time alone with books and in libraries as a kid. I was introduced to the more ‘serious’ side of literature when I was 11 by a teacher, Mr. Awde (who I have written poem about, which has just been published as part of Southwark Library’s Poetic Map of Reading project https://twitter.com/SouthwarkLibs/status/1534491301831397376?s=20&t=KLueLc2iYwG0V4X7tfAAQg) and that introduced me to a whole world of magic. I did a degree in English Literature (and Sociology) and, interestingly, apart from doing stuff about Romantic literature in the first year, and then Modern, Post Modern and Contemporary literature in which poetry was just a part of the courses, I generally picked the drama option as a specialism, except for one module called ‘British Poetry since 1940’. This was in 1984 – 5! I know all this as I’ve just dug out my course transcript! So poetry has been a bit of a ‘slow-burn’ with me, I think.

3. What interested you about the British Poetry option?

I think it was a combination of the Liverpool Poets and Ted Hughes. I truly loved ‘The Mercian Hymns’ by Geoffrey Hill. I think I was the only one in the class that did. Everyone else loved Seamus Heaney’s ‘North’ and I am sad to say that I didn’t really appreciate it, then. And, it was about the only course where there was actually a chance to study any women poets. Plath, naturally, but also Fleur Adcock, Adrienne Rich, Elizabeth Jennings, Anne Ridler, Patricia Beer and Elizabeth Bishop (these are the ones I remember). It’s a reminder of how things were when I notice that the last two on my list were two out of only three women poets (the other being Stevie Smith) in the anthology we used “The Oxford Book of Contemporary Verse 1943 – 1980”. The other 37 are all men.

Interesting in how Plath was subsumed into a British poetry course, by association with Ted as well!

4. Continuing on from your point about the imbalance between male and female in the anthology you had as a course book, how aware are and were you of the dominating presence of older poets traditional and contemporary?

Very. I was very politically conscious in my youth (and still). I got very fed up with all the traditional aspects of culture, and that’s why I chose all the post-modern and contemporary options going! I’d had my fill of Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, the early novel, Austen, the Victorian novel, Milton, Wordsworth, yadda, yadda, yadda by the time I was 18! I still, though, had, and have, a very soft spot for T. S Eliot and Ezra Pound and a lot of my poetry follows, or attempts to, the latter’s imagism. As I say, to me, then, contemporary theatre seemed to be where it was at, politically. I remember writing a stonking essay about the reception of Howard Brenton’s ‘The Romans in Britain’, which I’d seen just a few years before in 1980. I wanted things that challenged the worldview and poetry didn’t seem to me to be doing much of that. It was, though, I just didn’t have the patience to notice!

5. What makes imagism a radical point of view that challenges the accepted point of view?

I don’t think it is, necessarily, now, although it depends what the poem is trying to say. I was giving an example of canonical poets that dominate a syllabus.

But, in the sense that it was a movement that set out to reject the sentimentality and detached and second-hand cliches of Romanticism and Victorian poems, and advocated experimental forms and free verse, that’s quite radical for the time. The attempt to find a single image that gets to the heart or the essence of what a poet is trying to say is now part of the accepted way to write poetry, and in that the influence of the imagists has been huge, and that’s their enduring legacy. But I think people who aren’t big readers of contemporary poetry might still find things like lack of rhyme and so on means that it’s “not poetry”, so it’s still radical for them. I’ve certainly had comments from people about my poems not rhyming! I get the feeling that people find poetry a bit of a worry. That it will be “difficult” and in some way they don’t have the skills to “get” it, and that it will all be obscure and abstruse. I did a reading for a book club group recently, and that was something people said they were worried about – not having anything valid to say about it, and it being a difficult evening. Fortunately, that proved not to be the case and it was a really good evening with loads of interesting comments.

6. How did you decide on the order of the poems in your collection?

First of all, I knew I wanted ‘Terminal Velocity’ at the beginning. The creature lurking in the sediment – then striking.

I then knew I needed ‘Atavist’ at the end, as it has a little gleam of hope and healing in it.

Without going into too much exposition – I don’t want to impose “A Reading” onto them, but let others find theirs – I have sort of done them in a chronology which is personal to me.

And the most important bit is that they are all structured around “the songs”. Each song is from a woman of myth, real history or pop culture. And the idea is that they serve to comment on the action or mood of the pieces in between and move them into another phase.

7. How important is form in your poetry?

Traditional forms – I have been drawn to more this year. I struggled with them to start with, thinking them a restriction, and not really seeing what they could do for a poem – which may well just have been a reaction to my not being very skilled at them. So I kept trying, and one day – bing! – a sonnet happened, and it was pretty good. So I’ve done a few more of them and had a few published – both traditional and modern ones. I am struggling like anything at the moment with a villanelle. Why are they so hard? But I like the idea of a repeated form, which in terms of the subject I am writing about would be really effective, so I am going to keep thrashing about at it until it’s working. I also like working in couplets and tercets (rhymed or unrhymed) that often enjamb into the next one – I do this to hopefully create different layers of meaning and differences of pace.

Otherwise, I do like short forms of poems like haiku and micropoetry. With the tendency toward the imagistic, I find they work really well to encapsulate the essence of whatever it is I am writing about in a single image. Speaking of haiku, I have also grown increasingly to like the haibun, and I love the juxtaposition of prose with a haiku – it’s a really powerful form to combine a longer and more detailed piece of writing with something that either sums up the essence of it or encapsulates a moment of pure feeling.

Most of my poems look as though they are free-form, but I use what I hope are quite strong-but-subtle internal rhymes and assonance/slant rhymes. So that gives them a rhythmic structure. I also use white space to sort of “plot” where silence or pause-length or shift of (sometimes double) meaning happens.

8. What is your daily routine?

Generally (and this depends if it’s a paid work day or not, just in case my boss is reading), I will start at about 7.30am and begin looking at the poems that are already helf-formed, or at least started, and tweaking them about a bit. Once that is either finished or I get to a point where if I carry on it’ll just muck it up entirely, I start having a look at any notes I have made in my notebooks, or on my laptop. These will be little bits of ideas, words, phrases and so on that will hopefully spark off something that will turn into a poem. I do a lot of research, so most of the morning will be doing that and making any notes from interesting things (and trying not to Google myself down a rabbit hole). I will read someone else’s work before and during lunchtime. then carry on writing until about 4pm. Just trying things out, revising and so on.

If it is a paid work day, I tend to just have a look in the morning to remind myself what needs doing in the hope that a gobbet of genius will fall from the heavens at some point during the day. I keep a notebook next to me in case! I’m much more of a morning person so don’t do much later in the day. Again, a notebook is next to the bed in case something brilliant occurs to me in the night! Weekends is where I go out and about a bit more and getting into nature is really important for me. A lot of my poems have started off by something “found” that way.

9. How important is nature in your poetry?

Very. I live in a small rural village, and don’t get out much. When I do, it’s to the forest that surrounds me, my and other gardens, just looking at the sky – considering the small things and the infinite stuff. Because my job revolves around talking with people who live with trauma and mental health distress, I need to get away from people and talking. Getting into nature gives me solitude (of a positive sort) and peace. But also I think about (and write about) the darker side of nature…

One thing I regret is being about as far away from the sea, stuck more or less in the middle of England, as it’s possible to get. I’d like to get to the sea more, but it’s inside me.

10. What place do myths, legends and popular culture have in your writing?

Myths and legends a bit more than popular culture to be honest, which is interesting, as I used to teach media and film studies and love film! But many of my poems are prompted by more ancient stories (although you could argue that most movie genres are the playing-out of the same old myths, but that’s a lecture for another day). I read a lot of various myths from different cultures and the stories are such a rich vein of inspiration. Every year, I buy the “Country Wisdom and Folklore Diary” from Talking Trees Books and it’s got some fabulous snippets about local history and legend and customs, which has also provided me with some ideas. What I try to do with them is use them as a bridge between then and now. I’m interested in looking at the universal truths and universal behaviours depicted in myth and legend, and putting them into our world today. Not exactly magic realism but something in that vein. And the universal themes of violence, love, power, betrayal, loss, grief – there’s an awful lot you can get out of that as a poet.

11. What motivates you to write?

Getting (usually quite distressing) things out of my head, examining them, processing them, maybe even transforming them into something quite other, even something beautiful. It’s therapy, really.

12. What is your work ethic?

Get things done. And do them properly!

And then have a bit of a rest and try not to worry that you’ve done it all wrong.

I’d really like to do the one from the drummer in Spinal Tap “Have a good time… all the time” https://youtu.be/WrhzX3dRRiI maybe one day!

13. Most of the poems in your new collection are written in first person. What is it about this perspective that is so attractive?

I thought it was about 50/50, to be honest!

I think that it gives the opportunity to be direct in terms of conveying the emotion I want people to get from the poem and for some of that to transfer. As I am telling the stories in many different women’s voices, it was important to me to have that direct speaking/telling of them to the reader. They are saying, “Look. This is me. This is what has happened. This.” The ones where I want a bit of distance such as “Battered Woman” and “The Lodger” and are in the third person are no less emotive (I hope), but the distance created is there to emphasise the isolation and “otherness” of those women – that they are looked at but never really seen. And I hope the space then gives the reader a chance to examine how they may or society may have been complicit in that unseeing.

14. How do the writers you read when you were young influence your work today?

Maybe Walter Scott started off the whole legend thing!

I think that Pound and Eliot for the imagism, free verse stuff and the use of internal dynamics and rhythms instead of traditional form. Geoffrey Hill and Ted Hughes for the use of legends, myths, song and the bringing together of past and present, the sense of place and the dark side of nature and humanity. From the female poets I mentioned (several of whom, actually aren’t British – maybe they were on a different module?), particularly Elizabeth Jennings’ and Elizabeth Bishop’s sense of nature and something beyond it. Patricia Beer’s sense of grief and loss. Sylvia Plath’s pain and how to write it beautifully (or have a good try). .

Ah! I knew I’d forgotten someone really important – to add to my previous list – Penelope Shuttle. Her poems of pain, grief, loss abuse – tremendous. A lot has come from her.

15. Who of today’s writers do you admire the most and why?

Kim Moore – wonderful, powerful, subversive poems with wit and warmth as well. She uses experimental forms incredibly well. She is a terrific, vital poet.

Clare Shaw – luminous and beautiful, like incantations with beautiful images of loss and love and her use of internal rhyme is tremendous.

Andrew McMillan – honest, powerful and authentic. Brilliant use of white space.

Naush Sabah – really incredibly dexterous use of language, powerful and political and gorgeously intricate – and brave poems.

There are lots I am discovering all the time. I have a huge pile of reading to do!

What would you say to someone who asked you “How do you become a writer?”

Write!

Just go for it and see what comes out and don’t stop keeping on trying.

16. After having read your book what do you hope the reader will take away with them?

Some compassion. To look behind and beyond the surface of people who might seem “other”, “different”. To consider what it means to be lonely, to be isolated, to be victimised, hunted. To be somewhere where the only way out is by some kind of transformation, even if that is a wish, an addiction or it means no longer existing in or on an earthly plane. To know that there is still hope, still healing.

Supplementary Questions

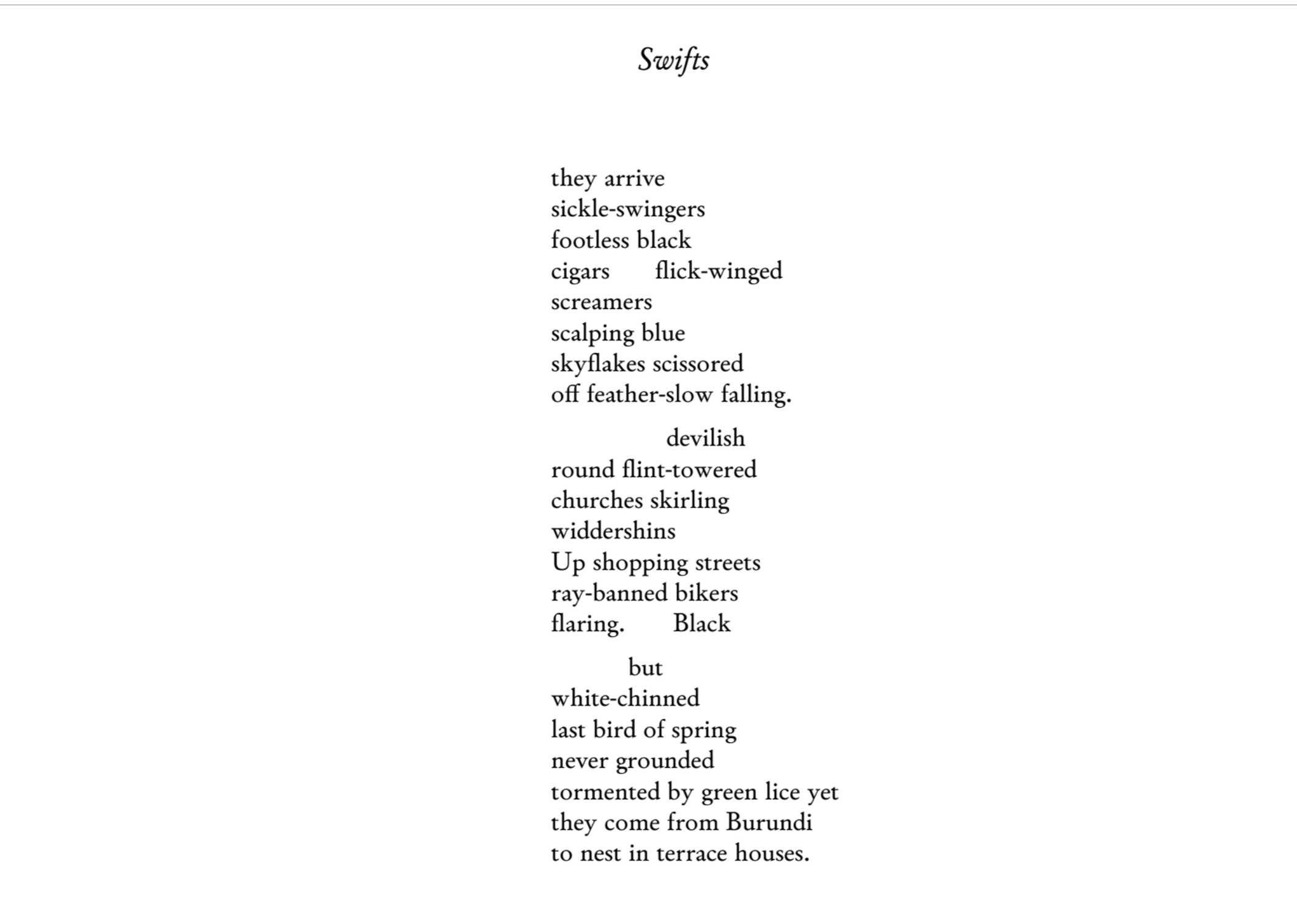

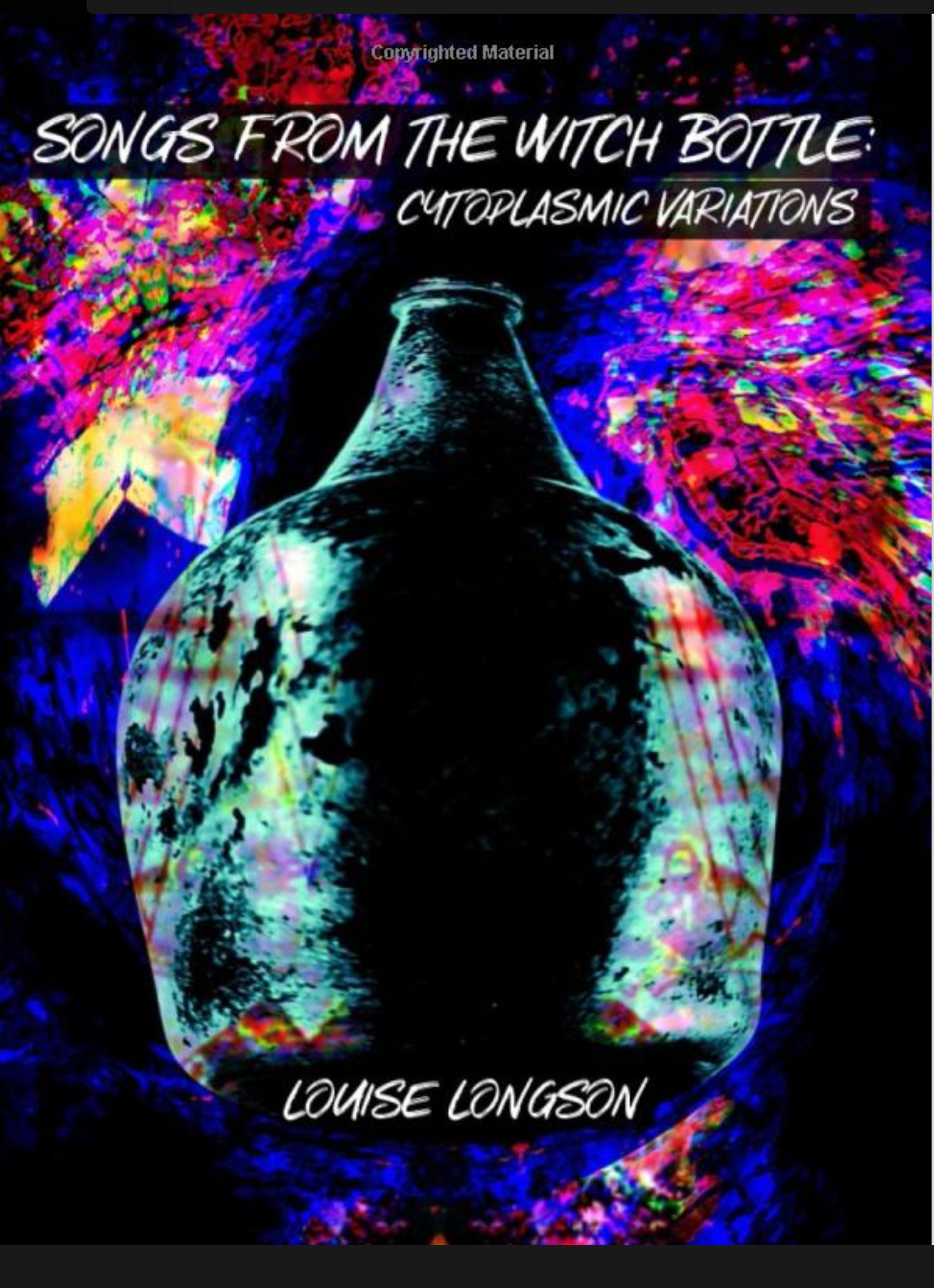

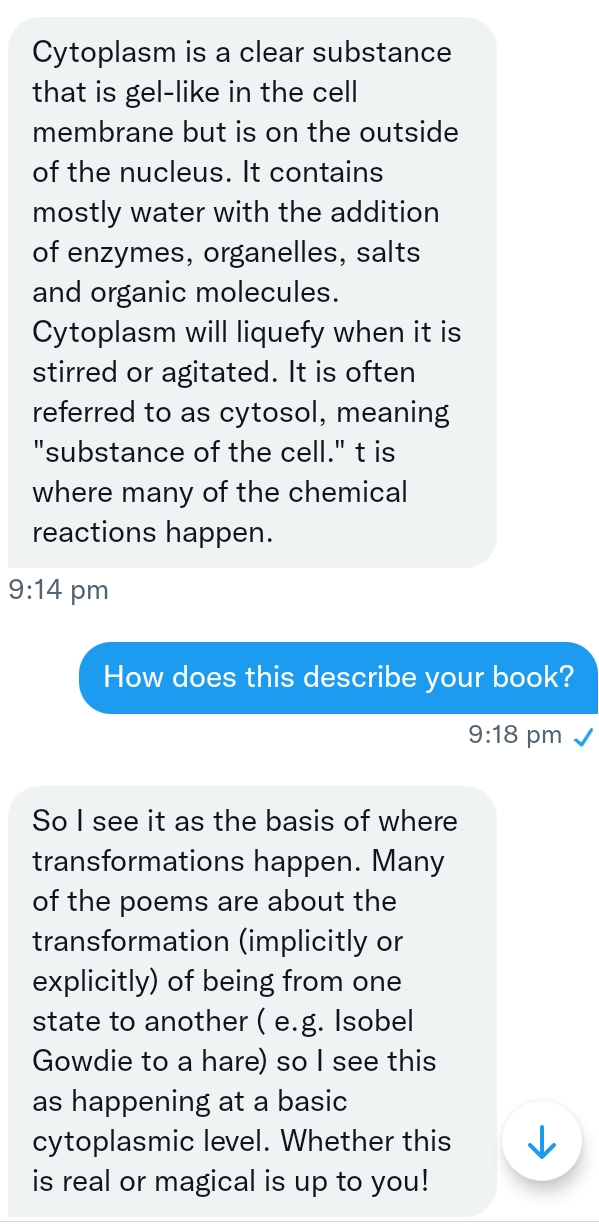

What are “Cytoplasmic Variations”?

Nigel Kent - Poet and Reviewer

– photo by Jane Dougherty

– photo by Jane Dougherty