Day Seven.

This Day, This Day

The man is old and frayed, with a thatch of snow-white hair. The eyes that used to hold such warmth and twinkled with merriment are unfocused. His memories are fragmenting, gradually being eroded like a seaside cliff pounded by sea and storms.

He makes his way across the lawn, heading for the vegetable patch. I catch up with him just in time to see him stretch out a hand to capture a ripe strawberry. It’s too far to reach and he topples into the middle of the French bean plants, grabbing at the wigwam of bamboo canes for useless support. He lands, sprawled in the soft earth, his legs tangled amongst the canes collapsed alongside him. Luckily he is not hurt but he’s struggling to get up. I help him to his feet and try to brush the mud off his jacket.

‘I’m all right, dear,’ he says. ‘Don’t fuss. Where did you go? Have you been shopping?’

We return to the house where he leaves a trail of footprints across the hall.

‘That wasn’t me,’ he says, as I fetch the mop, exclaiming in frustration. ‘I haven’t been in any puddy muddles. I can assure you, dear, that wasn’t me. It must have been the doggy.’

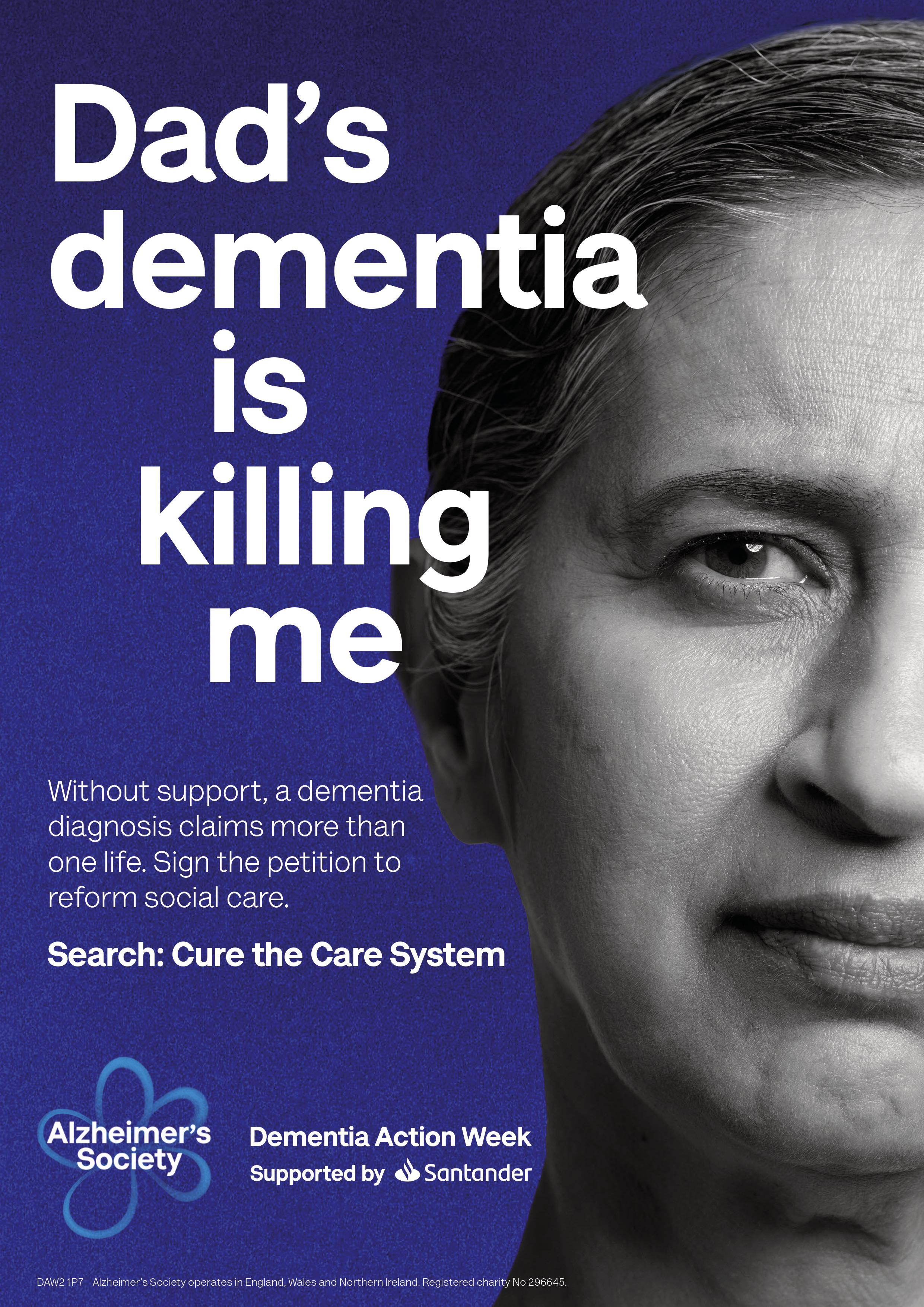

It’s a hooligan, this disease, this dementia cloud. It blocks everything out, hides the memories and chases away the sunshine.

‘Are you the nice one or the nasty one?’ Dad asks that evening. He is sitting on his bed and regards me warily as I come into the room.

The nasty one? Does he mean me? Of course he means me!

‘I’m sorry you’re going away from me, dear,’ he says sadly.

‘Going away, I’m not going away from you, Dad.’

‘The nasty one is.’

‘I’m sorry, Dad. I don’t mean to be nasty to you.’

‘No, no, you’re not nasty. You’re the nice one. But there’s a nasty one who sometimes comes. I want you back.’

Guilty as charged. I’m the nasty one who tells him off when he tramps mud all through the house, or walks about with a full coffee mug, leaving stains over the floor. He doesn’t remember the incidents, just that I’ve been cross. It seems that emotional memory is surprisingly resilient, lingering long after other memories have dissolved into mist. He wants the nice daughter who helps him to bed and brings him sweets.

As I sort his clothes for the morning, he watches me from mournful eyes. With his teeth removed and hair askew, he looks frail and vulnerable.

‘I’m sorry I was naughty, dear. I’ll try not to be naughty.’

It breaks my heart.

Memories are deceitful, treacherous things: the flotsam and jetsam of a life washed up on many shores and now left behind, like wreckage from a ship. He feels as if he’s sprung a leak. Ragged memories are spat out like seaweed. Words float away.

Who’s that?’ I ask, showing Dad a photo of himself with my mother. I go through these photographs with him every night in the hope of keeping at least some memories alive. ‘Who’s that good-looking man?’

‘Oh I know him ever so well – I can’t think of his name.’

‘It’s you, Dad!’

‘Is it? Oh, yes, that’s right,’ he replies calmly, not at all embarrassed.

‘Who’s the lady?’ I continue.

‘She was the one in London. I can’t remember who she was.’

‘That’s your wife, Dad. My mother.’

‘I wasn’t married to your mother, was I?’

‘You were,’ I tell him. ‘But it doesn’t matter now.’

It’s a maze. He can’t find the way out. He’s in the dungeon of his self.

It’s gone midnight and not long since I managed to get Dad settled in bed. The alarm is squealing from above the open door to his room. Now he is standing in the doorway in his pyjamas, his still abundant hair sticking out in clumps like an old brush.

‘What’s the matter, Dad? Are you all right?’ I ask.

‘I can’t find the bed.’

‘But you were in it just a few minutes ago.’

‘Was I? Well, where is it now?’

‘It’s in this room. We’ll soon get you back in.’

I help him back into bed and refill his bowl of sweets. He immediately takes one and hides it under his pillow. As I tuck the sheets around him, he reaches up to give me a hug. ‘You’re my favourite dog,’ he says.

‘And you mine,’ I say. ‘The best.’

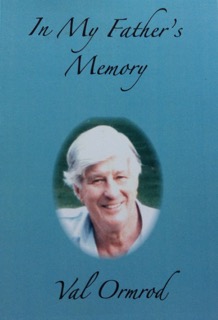

Val Ormrod

(First published by Gloucester Writers Network, 2017)

This short piece contains extracts from the memoir In My Father’s Memory, published 2020

On the Locked Wing

They’re not prisoners of course!

Ha ha

No, not the lift

There’s a code you see

Oh they brought you wine

How lovely!

Never mind

We’ll look after that

There’s a beautiful garden!

No, you can’t go out

There’s a code you see

Let’s go to the lounge

Nice and warm in there

No, not that way!

He’s a funny one, isn’t he?

Baked potato? No?

Never mind

Soup tomorrow!

Where are you going?

Let’s go back to your room

Nice and warm in there

There’s a code you see

I’ll be back in a minute

(I won’t be)

They’re not prisoners of course!

Ha ha

He’s a funny one, isn’t he?

-Nina Parmenter (. I wrote it after a visit to my father-in-law on a dementia wing in a care home, and it’s a found poem really, compiled from things I heard the carers say. I guess it comes across slightly comical, and it is, and it really isn’t. )

Rest Cure

Here’s Jack, lanky in a cut-down suit, narrow-chested but chippy as life in the rattle scrape east end of Montreal can make an English-speaking kid. He’s got Catholicism in common with the French kids, but they want to know “es-tu canadien or es-tu anglais?” They push; he pushes back.

He doesn’t go looking for a fight, though, not like Ger. A year and a half older, Gerry is shorter than Jack but solid and scrappy. Real tough. Tough enough to take down a big guy older than him. Boys and men crowd round to watch him fight—even the guy’s father, hands by his sides, face like an old sock, or a crumpled handkerchief. Jack asks, “why don’t you stop it?” The man shrugs, real tired looking, says it’s a lesson. Next time the son will watch who he picks on.

Katie and Helen are working. They have good jobs at the hospital, doing research for a doctor, mixing things in labs, making people well. The doctor made a big impression on his sisters, talking about people dying of the consumption, and not enough beds for them all. The charity wards are full, and the rest cure is the only thing for bad lungs. Worried about his cough, the girls pulled strings for him. That’s how Jack ended up in this place, like a bump on a log. The doctors call it ‘chasing the cure’, but Jack knows that’s a load of bull; you can’t chase anything when you’re lying still.

Blue dome, often white-streaked, often grey. You don’t see a sky like that in the city, and his mother and the girls are agog over its beauty when they come to see him. They make the same winding train trip Jack had taken, steam whistle wailing, sounding lonely as hell, and that’s how he feels in this bed, this basket on wheels. He has to lie here all the time, on this porch and in the dark night, dormitories full of the snores and farts of strangers, old men and young ones, many no older than Jack.

The dome is a blue bowl, inverted, held up by the mountains. On the porch, lying there with the other patients, all in a row, Jack feels the air, cold and oh-so-good-for-you fresh. Out with the bad air, in with the good. But if he’s got to chase a cure, he’d rather be chasing it the way the kids on the block used to chase each other. The way they’d chase the precious puck the French kids stole from them, leaving them—Jack and Ger and the guys on Rachel Street—with nothing but horse turds to play shinny with.

Some of the people are really sick, skeleton skinny, coughing themselves hollow. Jack measures the distance down the slope toward the lake when one of them starts coughing. Others are like Jack, here because… Jack is hard-pressed to say exactly why he’s here. There was whispered talk in the pantry over the dinner dishes, Ma and sisters that worried about him. The consumption is in the family. Aunt Claire died of it five years ago. Whispering over weak-chested, tall and gangly Jack, growing so quickly that his wrists stuck out from the sleeves in the suits Ma made by cutting down their father’s old police uniforms. The old man left a couple of uniforms when he died, the last Ma will have to work with.

How could they send me away? he wonders; I was just starting to make money at the factory, dammit. Man’s money, almost. Not like the message-boy money they were so proud to hand over to Ma when he and Ger worked at the Birks building.

They’d sit in that narrow dusty room with its wood floors that creaked, itching for the bell to ring, to spring them, he and Gerry each waiting a turn to carry something, a message or a parcel, it didn’t matter. To be out running, just flying, through the building, down the alleyways. Ger would beat him to the bell, especially when the message had to go far. They’d wind up wrestling and rolling around on the floor. Jack got the worst of it, Ger was that tough. Beat Jack up bad one time. Ma wanted to know what happened to his face, so Jack told her the French kids did it. Katie didn’t like them fighting, not at all. She was the one who got them the jobs, in the building where she typed all day.

Now she and Helen are working for that doctor. That’s how he got here, the girls put in a word. Ma told him how lucky he was. Lots of people with the consumption, dying of it like her sister, and never enough beds. Less than a hundred here, and a smaller place on the other slope for the Jews, that’s what Albert tells Jack when they first get talking.

Albert used to be a patient. He caught the cure, but he’ll never be well enough to go back to the foundry. They let him work here. He does odd jobs, pushes the meal cart. He wheels beds out onto the porch every morning and every afternoon for the patients to take the air, wheels them back to the long sleeping rooms.

This is no place for me, Jack thinks. It’s fine for the rich snots to lie there reading their newspapers and fat books. They’re used to sitting around, to having some flunky bringing them their breakfasts. No big deal to have metal enamel basins brought in so they can wash and shave. Service like that is a big deal for Jack. He started shaving last year. He’d break the ice on the bucket, the way their grown brothers had, when he and Ger were whippersnappers watching them. No one ever brought him a basin before.

It’s cold on the porch sometimes, other times hot. Buzzing hot, but all Jack keeps is cold. He feels it in his young bones, feels the days line up like boxcars on a siding: waiting to be wheeled outside, waiting to be moved indoors. Nothing ever new except when the doctor walks through, his coat snapping behind him. And visiting days, his sisters going on about people in the parish, Ma sighing over how the mountains remind her of being a girl in Ste. Sophie. It’s always the same slow rhythm. At what point does blue streaked with white become white streaked with blue, a milky bowl?

Once in a while, they bring a different basin and he has to spit. There’s no blood, never. Albert will say that Jack had none of those germs, the ones that make the consumption, but not until much later when he helps Jack pack his grip.

Albert jokes with Jack. He calls him the sleepwalker. Pretends Jack’s last name is Dempsey. He’s talking about those first few nights when Jack would get out of bed. He wasn’t doing anything bad—just got up to peer through windows, see what his feet looked like in the moonlight, find out what was beyond that door. It took two orderlies to strap him down, he fought the ties so. Albert puts down the putty knife he’s using for the storm windows, throws his arms and head around, laughing. His hands are open fists. The big orderly, Charlie, finally landed one good punch, Albert says, and Jack didn’t give them any more trouble. Now he settles down peaceful as a babe every night.

It’s long ago to Jack, but the nurses still pin him with their sharp gazes. Not that there’s anything he could do in the white shift they traded for his suit, nowhere he could go. Snow sprawls on the mountains beyond. Sometimes the hillsides are green, sometimes parched like a faded yellow blanket, but always they slope away, out of reach.

He thinks about his family. Ma off to Westmount every day, to do for Mrs. Marler. She brings home Mrs. Marler’s old clothes, still perfectly good, for the girls. Brings home Mrs. Marler’s ways: doilies on the arms of the sofa, and pass the peas please. His father would slam his fist on the table so the dishes rattled, mouth pursed, his voice shrill: “Mrs. Marler, Mrs. Jesus Marler, for crissake!” But the old man is gone. The pleurisy took him in less than a month, leaving just two sets of uniforms for Ma to make over.

The girls are smart in Mrs. Marler’s made-over clothes. Katie and Helen have good paying jobs. All the girls play piano, like Ma. They have manners like Mrs. Marler’s daughters.

The older brothers are grown and gone to the lumber camp or the merchant navy. Gerry never comes to visit Jack. Scared of the germs, Helen says. He wants to come but he can’t, Katie says. He’s apprenticing with a tile-setter. He’s home only for bed, and for the meat and cold potatoes Ma puts aside on the hob. Time off for Mass, of course.

It doesn’t sound much like Gerry to Jack. He can’t imagine Ger working hard, toeing the line. But everyone has to pull their weight now the old man’s gone.

So, why send Jack away when he’d started to make real money? On the delivery run, he’d race up and down stairs with boxes full of stockings in their paper packets, so quick that Ernie hardly had time to finish his smoke. He taught himself to drive by watching Ernie’s feet work the clutch, the brake, the gas. Ernie sometimes let him drive back after the last deliveries. And the factory paid better. Those three months when he had a fatter pay envelope to carry home to Ma, he didn’t mind the big room steamy from the vats, nor his fingers wrinkled and hands cramped from putting wet stockings on the forms.

He thinks about Ger working with the tile-setter, handing him tools, learning how to make the pieces go in straight. He has to make himself not think about Ger. He looks at the slice of lake he can see from the porch, counts the trees that block his view, looks at the sky. There’s always the sky, even when it’s years he has to count.

It’s nearly spring again when Jack finally puts his suit back on, feels fabric strain over his chest when he does the buttons up. He rides the train back to the city alone, just like when he came. He never once tested positive, not once in practically a year. That’s what Albert tells him as he leaves.

The factory’s not taking on any more men. Jobs in the city are harder to find. Jack takes work far away. He goes to the Gaspé, then up north in Ontario.

The north is snow crunch and fly buzz: Deep River, Chapleau. Each town another tie on tracks that rumble and hum, go on and on. Every place a stretch of cold distance, whether there’s white or green beneath the blue dome. A rackety churn, no rest.

He doesn’t see the family often. He looks for stillness in gold-brown liquid at the bottom of a glass, in the gentle burn that starts in his stomach. He drinks in rented rooms in railway towns, or in bars, at tables a little away from the lumberjacks who sing and swear and down glasses, though not with the railwayman. Not with Jack.

Montreal, when he goes back for visits, is all noisy bustle. Hugs from Ma and sisters, little nephews and nieces, slaps on the back and nights in the tavern with Ger. He pulls Gerry out of fistfights, or backs him up. When they put on uniforms, they make a fine pair: the tall one and the short one, Air Force and Army. Both broad-shouldered now, and sharp. They turn a head or two.

Then a different trip. Back, for Ma’s funeral. Telegraph poles tick by and the train jostles. The rumble of the tracks builds. There’s pressure in his ears and behind his eyes. Tightness rises from his chest to his throat, squeezes, chokes him. A swig or two from his flask helps, but he doesn’t dare drink more. He won’t shame the family at the funeral.

But afterwards, his brothers-in-law gone home after only one round, Jack roars through the taverns. With Ger shipped out to England, it’s not like it was. He just drinks until he stumbles back, waking his sister’s house, roars some more, drops and sleeps.

The next morning, there’s little Maureen showing her brother the hole Uncle Jack punched in the wall. His head is muzzy, and he’s anxious to be on his way, furlough over. He carries the train’s rattle with him to where his unit is stationed.

The buzz stays in his head long after the C.O. comes to the barracks with the news. Gerry, killed overseas. Didn’t even see action, poor bugger. An enlisted man pulled a knife on him in a barroom fight.

Jack never makes it home again. It’s all motion, for years and years, all a thunderous blur. He knows other cities, lives in one with a view of mountains that make the Laurentians seem like hills. He meets someone at the office where he’s taken a job. She’s a woman from Toronto, but Catholic, and they start keeping company. She agrees to marry him though they think they’re probably too old to start a family. To their surprise, a baby girl arrives after they’ve moved to another new city.

He puts down the bottle because his wife says he must. He gets dry and stays dry. There are groups she wants him to go to. He tries them, but it’s all talk. So he goes it alone, never takes another drink.

They have another daughter. Their last move is to the prairie, where the dome stretches so wide and blue there are no hills to be seen.

The blinds half-lowered, the blue or milky blue or grey outside is shut out to allow him and the others, all in their chairs, a discreet snooze. They’re all old, and mostly women. The people who work here don’t strap him down. They did in the hospital when it hurt so bad to cough and his chest was full—pneumonia, they said. He kept wanting to sit up and catch a breath. But he didn’t fight the ties, just worked and worried at them until he came here.

What he is doing in this place, so still and quiet? He has a department to run, a family to see to, man’s responsibilities that he shoulders gladly. His children visit, with pictures of their mother. Bitter is the word he finds as he realizes he remembers nothing about her. They remind him again, but gently, that she died last year.

The girls are doing well. He’s proud of them, their good jobs. It was their doing, he remembers now. They brought him. A fine daughter on either side for the long ride—he glowed with pride. But why the hell must he stay here with these old women, staring at flickering colours on a screen?

It’s still now. Jack hears the women’s voices, the quiet clatter of cutlery—but at a distance. The years slope away.

-Francis Boyle (from her recent collection, Seeking Shade. An earlier version of the story won 3rd place in a contest called The Great Canadian Literary Hunt, and was published nearly a decade ago in the online version of This Magazine (yes, that’s the name of the mag): https://this.org/2011/11/23/lit-hunt-2011-rest-cure-fiction-frances-boyle/

“Death’s Grace”

On the other side of the world

A mother’s soul grows childlike

While her body withers and shrivels

Under the blankets and darkness

Of curtains and closed doors

Waiting for God’s grace

Or Death’s.

September 5, 2019

My step-mom passed away on October 30, 2019.

-Mike Stone

The Unresolveables, a fifteen sonnet heroic crown

13. I Come to

“Did I come to this place with things of mine?”

Powered attorneys brought Pam’s belongings,

her husband having died in the meantime.

Soon, all will be unbelongings.

Belonging only in the heads of those

who knew her. She will leave her words, art:

sketches she made of her three cats of whose

names: Hoppy and Missy, she knew by heart.

It is sad to talk of someone living

as if they have already passed away.

Some relatives are shocked to find filling

body of one they knew is a strangers gaze.

Professional, you can’t help get close: her rhyme:

“Is that wave for mine? Is it now my time?”

14. Wave For

“Is that wave for mine? Is it now my time?”

Pam talks of ocean as taker away

of value she’s gathered on the shoreline.

Unaware others are with her each day.

A strange time for all, when keen avoidance

of others has been the key to our health.

We have felt loss sharply, hugs and street dance,

a dosey do, a time outside ourselves.

Locked in Pam is a stranger to all this,

perhaps she has noted the extra cleaning,

masks so she can’t see our smiling faces.

Her world smaller, stranger each new morning.

I’ll leave the final words to her: she sings

“Sat at tideline with all my belongings.”

15. The Unresolvables

Sat at tideline with all my belongings.

My photos, my ornaments, all gathered

against receding waves that keep pulling

all away from me, memories tethered

by my frantic grasp to prevent their drift

into forgottenness. They are reminders.

How did I find myself here, a spindrift?

Water’s edge or earth’s end? Which is kinder?

Only strangers now, who say they know me.

Hold my hand, take me down long corridors.

They have photos. It looks like me, Nowhere

I can recall. How did I reach these shores?

Did I come to this place with things of mine?

Is that wave for mine? Is it now my time?

-Paul Brookes

Bios and Links

-Frances Boyle

is the author of Seeking Shade (The Porcupine’s Quill, 2020), a story collection, shortlisted for the Danuta Gleed Award and the ReLit Award, and a novella, Tower (Fish Gotta Swim Editions, 2018), as well as two books of poetry, most recently This White Nest (Quattro Books, 2019). Her poems and short fiction have been published throughout North America and internationally. Frances hails from the Canadian prairies, and now lives in Ottawa.

-Alice Willitts

is a writer and plantswoman from the Fens. She is the author of With Love, (Live Canon, 2020 – winner of the Live Canon Collection competition) and Dear, (Magma, 2018 – winner of the Magma Poetry Pamphlet Competition) and holds an MA in Poetry with Distinction from the University of East Anglia (2017/18). She leads the #57 Poetry Collective and is collecting rebel stories in the climate emergency for Channel Mag. Guest editor of Magma 78 on the theme of Collaborations (2020) Author of Think Thing: an ecopoetric practice (Elephant Press, 2020). She’s a founding member of the biodiversity project On The Verge www.onthevergecambridge.org.uk.

alicewillittspoet.uk

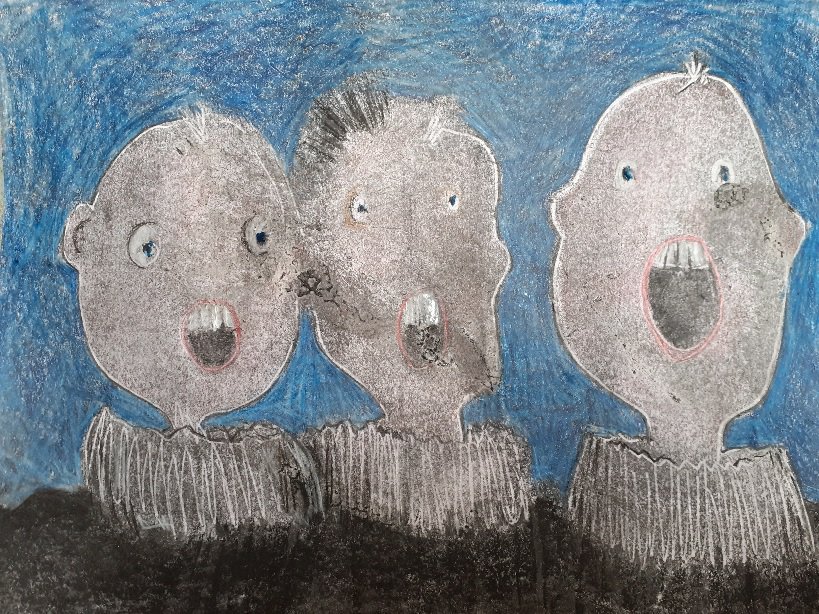

-Stevie Mitchell

I want to show my stories simply, but at the same time in an unexpected way…

He is a Derbyshire-based artist and illustrator creating captioned drawings, fragments of stories and uncanny happenings, presented under the collective banner, INKY CONDITIONS. He works with ink and brush and some deliberately lo-grade technology. Amongst a playfulness, themes of personal loss emerge. Part therapy: a loving and cathartic catalogue of everyday life – and death.

Stevie shows and sells INKY CONDITIONS work at arts trails and fairs across Derbyshire and Staffordshire, including the Wirksworth Festival. Alongside this, he works as an independent commercial illustrator, making useful drawings for beer branding, businesses, and for Barnsley Museums, including visitor guides and poetry anthologies.

Website: www.inkyconditions.co.uk

Instagram & Twitter: @mitchsteve / #inkyconditions

Frances Roberts Reilly

is a poet and filmmaker. She began writing seriously whilst working at BBC television in London, England. After making award-winning documentaries, she earned an Honours degree in English Literature at the University of Toronto.

Frances has an international profile as a Romani writer. True to the spirit of the Romani diaspora her poems, short stories, articles have been published internationally in well regarded anthologies in Canada, U.S., U.K., Wales and Europe. Her poetry has been featured by League of Canadian Poetry’s National Poetry Month and Fresh Voices online.

Her books include Parramisha (Cinnamon Press) and The Green Man (TOPS Stanza Series). Chapters from her memoir Underground Herstories have been published in Literature for the People and the Journal of Critical Romani Studies, Central European University in Budapest. Frances was invited as guest panelist on the Gelem, Gelem — how far have we come since 1971? program as well as participating on a literary panel of Romani women writers at the World Romani Congress, 2021.

Frances has been a guest author on CBC Radio and WSRQ Radio, Sarasota. She is the Producer of radio documentary series, Watershed Writers on CKWR FM 98.5 Community Radio.

Frances lives in Kitchener, Ontario, Canada.

– Lauren Thomas

is a Welsh poet whose most recent writing is in The Crank Literary Magazine, Briefly Zine, Re-side Magazine, Abridged and Green Ink Poetry. She has poetry forthcoming in Dreich’s Summer Anywhere anthology, Songs of Love and Strength by TheMumPoemPress and was winner of Poems for Trees competition with Folklore publishing. She is an MA student in Poetry Writing with Newcastle University and The Poetry School, London.

laurenkthomas@co.uk

Twitter @laurenmywrites

Instagram @thoughtsofmanythings

-Val Ormrod’s

poetry has been published by Eye Flash, Hedgehog Poetry, Graffiti, Hammond House, Gloucester Writers Network and in several anthologies. In 2019 she won the Magic Oxygen International Poetry Prize and Ware Poets Open Competition, was shortlisted for the Plough Prize, Wells Festival of Literature and nominated for the Forward Prize single poem award. Her memoir In My Father’s Memory was published in 2020.

–Stephen Claughton

was interviewed by The Wombwell Rainbow in April last year. His poems have appeared widely in magazines and he reviews regularly for London Grip. This is a poem from The 3-D Clock, a pamphlet about his late mother’s dementia, which Dempsey & Windle published in 2020. Copies are available from their website here.

-Fiona Perry

was born and brought up in the north of Ireland but has lived in England, Australia, and New Zealand. Her short fiction won first prize in the Bath Flash Fiction Award 2020 and was shortlisted for the Australian Morrison Mentoring Prize in 2014 and 2015. Her flash fiction performance won second prize in the Over the Edge Fiction Slam 2021. Her poem, “Fusion”, was longlisted in the Fish Poetry Prize 2021, and she contributed poetry to the Label Lit project for National Poetry Day (Ireland) 2019. Her poetry and fiction has been published internationally in publications such as Lighthouse, Skylight47, Spontaneity, and Other Terrain. Follow her on Twitter: @Fionaperry17

Her first collection, Alchemy, is available from Turas Press (Dublin).

-Margaret Royall

is a Laurel Prize nominated poet. She has been shortlisted for several poetry prizes and won the Hedgehog Press’ collection competition 2020. She has two poetry collections:

Fording The Stream and Where Flora Sings, a memoir in prose and verse, The Road To Cleethorpes Pier and a new pamphlet, Earth Magicke out April 2021. She has been widely published online and in print, most recently: Hedgehog Press, The Blue Nib, Impspired & forthcoming in Sarasvati and Dreich.

She performs regularly at open mic events and facilitates a women’s poetry group in Nottinghamshire.

Website: https://margaretroyall.com

Twitter: RoyallMargaret

Instagram : meggiepoet

Facebook Author Page: Facebook.com/margaretbrowningroyall

–Annick Yerem

lives and works in Berlin. In her dreams, she can swim like a manatee. Annick tweets @missyerem and has, to her utmost delight, been published by Pendemic, Detritus, @publicpoetry, RiverMouthReview, #PoetRhy, Anti-Heroin-Chic, Rejection Letters, Dreich, 192, The Failure Baler and Rainbow Poems. https://missyerem.wordpress.com. https://linktr.ee/annickyerem

-Nigel Kent

is a Pushcart Prize nominated poet (2019 and 2020) and reviewer who lives in rural Worcestershire. He is an active member of the Open University Poetry Society, managing its website and occasionally editing its workshop magazine.

He has been shortlisted for several national competitions and his poetry has appeared in a wide range of anthologies and magazines. In 2019 Hedgehog Poetry Press published his first collection, ‘Saudade’, following the success of his poetry conversations with Sarah Thomson, ‘Thinking You Home’ and ‘A Hostile Environment’. In August 2020 Hedgehog Poetry Press published his pamphlet, Psychopathogen, which was nominated for the 2020 Michael Marks Award for Poetry Pamphlets and made the Poetry Society’s Winter List.

In 2021 he was shortlisted for the Saboteur Award for Reviewer of Literature.

To find out more visit his website: www.nigelkentpoet.wordpress.com or follow him on Twitter @kent_nj

-Olive M. Ritch

is a poet originally from Orkney. She was the recipient of the Scottish Book Trust’s Next Chapter Award 2020 and in 2006, she received the Calder Prize for Poetry from the University of Aberdeen. Her work has been extensively published in literary magazines, anthologies and websites including Poetry Review, Agenda, The Guardian, New Writing Scotland, The Poetry Cure (Bloodaxe) and the Scottish Poetry Library. Her work has also been broadcast on Radio 4.