Wombwell Rainbow Interviews

I am honoured and privileged that the following writers local, national and international have agreed to be interviewed by me. I gave the writers two options: an emailed list of questions or a more fluid interview via messenger.

The usual ground is covered about motivation, daily routines and work ethic, but some surprises too. Some of these poets you may know, others may be new to you. I hope you enjoy the experience as much as I do.

Steve Denehan

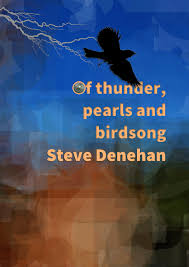

lives in Kildare, Ireland with his wife Eimear and daughter Robin. Publication credits include The Irish Times, Poetry Ireland Review, The Phoenix, Into the Void, The Opiate, The Hungry Chimera, Ink in Thirds, Crack The Spine and The Cape Rock. He has been nominated for The Pushcart Prize and Best New Poet and his chapbook, “Of Thunder, Pearls and Birdsong” is available from Fowlpox Press.

Here are some relevant links:

Website – https://denehan.wixsite.com/website

Twitter – https://twitter.com/SteverinoD

Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/denehan

Steve performs his poetry at iambapoet.com

https://www.iambapoet.com/steve-denehan

The Interview

- When and why did you start writing poetry?

I started writing poetry when I was in primary school. I was lucky enough to win a small competition when I was around 9 years-old. My (very) short story was published in a national newspaper and I won a crisp £1 note. My father was a carpenter and worked so hard to provide for us and I remember being amazed at how he gave sweat and sometimes blood to turn wood into money whereas I had taken what was in my head and turned that into real, actual money. I thought, JACKPOT!

This would have been in the mid-1980s in Ireland and unemployment was very high. Times really were tough and my parents thought that writing wasn’t really going to give me much of a future. So I was discouraged from writing all the way along really. I can understand their thinking of course but I still wrote bits and pieces over the years.

I would have written with zero discipline and really with no objective. I just got a kick out of it. It’s still the same now really. I wrote short stories, poems and a few screenplays purely for the joy of it. My wife Eimear had tried for years to persuade me to submit the poems somewhere but I assumed that it would be just a waste of time. I would never have, and still don’t, consider myself a “writer”. I just like to write. Eventually Eimear wore me down and I put together a submission and sent it out. I absolutely expected it to be rejected so I put it out of my mind. If it had been rejected I doubt I would have ever tried again but, amazingly, a poem was accepted and published.

I was astonished and was sure that there had been some mistake. Until I saw the poem appear online I didn’t really believe it. This would have been just over two years ago. It seems strange to think back now but at the time I remember thinking that I had gotten further than I ever would have expected and I was happy to leave it at that. Sometimes when I think back to that time (and so many other times in my life) I want to give myself a shake.

Happily, I was persuaded to submit to a few other journals and got lucky again and I just kind of continued. Since then, and I still can’t believe this, I have had just under 200 poems published in print and online all over the world and a chapbook published which I still hold in my hands every once in a while, just to be sure it really happened.

The writing, like so many other things in my life, is something I just kind of fell into and I get an enormous amount of pleasure from it.

- Who introduced you to poetry?

An old teacher of mine, Mr. Shanahan. When my chapbook was published I got in touch with him after all these years to give him a copy as, if I had never met him there would have been no poetry and probably no writing full stop. Everyone seems to have a favourite teacher but Mr. Shanahan was more than that to those lucky enough to be in his class. He was, and still is, an amazing person who has an infectious enthusiasm for, well, everything.

He introduced, what he called, “Poetry Corner” every Friday where everyone was encouraged to write a poem and read it. In a classroom of boys only this was no mean feat but it didn’t take long before it was the highlight of our school week. We were taught how poetry could be anything, it could be personal or a complete fiction, it could rhyme, or not and it could be as long, or as short, as we wanted. It was fantastically freeing. I still remember the poem he read to us that he said was the shortest poem in the English language. It was called “Goldfish” and the whole poem was, simply, “wet pet”.

Besides having Mr. Shanahan we were also privileged to have a child prodigy and one of Ireland’s greatest poets in our class, Davoren Hanna. Like Christy Brown before him he had been born with a tremendous disability, quadriplegic cerebral palsy. He could not communicate verbally and could do nothing for himself yet within him was a burning intelligence that shone brightest through poetry. Sitting on his carer’s lap he would slowly lean toward oversized letters written on a large board, painstakingly creating some of the most wondrous poetry ever to come out of Ireland. Sadly he passed away in his late teens but his work lives on and is still absolutely transcendent. I wrote a short poem about Davoren actually if you would like to read it.

Davoren Hanna

A poem for one of Ireland’s greatest poets and, once, my friend

the wheels of his wheelchair squeak along my femur

he taught me

how words are an upturned collar against it all

he planted shame

behind my ear when I let him go

before he went

my body shared

my thoughts borrowed

and words, these little, late words

broken piano keys on the ocean floor

- How aware are and were you of the dominating presence of older poets traditional and contemporary?

I was not aware at all of the dominating presence of any other poets… But I guess I am now! Thanks for that Paul! Maybe it is because I write only for the love of it that I am oblivious to any shadows cast by anyone else. In the best possible way I really don’t care about what anyone else is doing or has done as it is not going to affect what I am doing. I am going to write regardless. I probably shouldn’t admit to this but I don’t really read a whole lot of poetry and never have. I listen to, and am often moved to tears, by song lyrics though. I find songs have a much greater impact on me than poetry.

- What is your daily writing routine?

My daily writing routine can be quite varied. It all depends on what, if anything, is going on in my head. I don’t seem to have a plan at all. Usually a line will come along based on something that has happened or that I have seen. I either take note of the line somewhere and come back to it later or, if time allows, write the poem on the spot springing off that one line. I often find that when I have written one poem another poem is ready and waiting so I tend to write several back to back. Once a poem comes along I find it is usually finished quickly. I don’t think I have ever spent longer than half an hour on an individual poem. I have met some really nice people through poetry and they can pour over a poem for days and weeks before it is just right. I have a huge amount of admiration for them and how they work. I have tried to spend more time honing a poem but they seem to lose whatever flow they might have had.

5. What motivates you to write?

I know a lot of people say that writing is a way of exorcising. I’m sure has been true for me occasionally but really it simply comes down to the joy of it. The idea of creating something that wasn’t there previously is weirdly intoxicating. It doesn’t even have to be good, luckily! There is an alchemy to it all. Taking thoughts and giving them some kind of life is incredible. They don’t even have to go anywhere. I have hundreds of poems that I have never submitted anywhere and probably never will but I am so happy that they exist. Though in saying that I never go back and read them again. At the risk of sounding ridiculously pretentious it is the act of creating them that is so addictive.

6. How do the writers you read when you were young influence you today?

I’m not sure really. I think I am probably more influenced by what and who I read now. The influence of the writers I read when I was younger has probably waned a little, or a lot, over time. Like my approach to writing I read only for pleasure and as a result I read (and probably write) a huge amount of nonsense.

7. Whom of today’s writers do you admire the most and why?

I absolutely love Glen Duncan and would encourage everyone to track down any of his books but particularly his startling debut, Hope, the devastating Death of an Ordinary Man and the darkly funny and dazzlingly inventive I, Lucifer. He has a way of putting the reader right in every moment and is so, sometimes frighteningly, relatable.

I also gobble up as much Joe R. Lansdale as I can though he is so prolific that he almost writes them faster than I can read them. In terms of variety there is nobody like Joe who can flit effortlessly between Elvis and JFK teaming up and fighting a re-animated ancient Egyptian mummy in Bubba Ho-Tep to the achingly beautiful and tender, The Bottoms, which could have been written by Mark Twain.

Paul Auster is another favourite but I feel he has faded a little over the last fifteen years or so. His earlier stuff was so beautiful and thought provoking and didn’t take itself as seriously.

They would be three contemporary writers who I would love hugely but there are many, many others.

9. What would you say to someone who asked you “How do you become a writer?”

I would say, “I’m not sure, ask a writer!” Really, the beginning of the answer is unbelievably simple I think. Just write. Beyond that I find that the two most important things for me when it comes to writing is to only write when I have something to say and to place more importance on content than style.

If you have written a few bits and pieces and feel that you would like to submit them I would recommend doing a little research beforehand. There are an almost infinite amount of journals and magazines but some might suit more than others. Also, feel free to reach out to me, or any other people out there who are writing, for advice. From my experience everyone is really warm, open and helpful and will gladly help steer you in the right direction while avoiding the pitfalls.

10. Tell me about the writing projects you have on at the moment.

I would love to dazzle you with a long list of interesting and impressive projects that I have going on at the minute but really I’m just writing away and seeing where it takes me. I have some poems coming up soon in a few amazing places like Into The Void and Poetry Ireland Review as well as a batch of poems that are coming out in the autumn in the amazing and artful language of Farsi. A couple of weeks ago I was shortlisted for the Anthony Cronin International Poetry Award at the Wexford Literary Festival but unfortunately didn’t win. It was a great experience though. I had been due to have a book published in September but I ended up withdrawing it as I found the publisher very, very difficult to deal with. That was a real shame and a painful thing to have to do as there is no guarantee that I might ever have the chance again. But I am glad I did as I want my poems to appear somewhere where they are wanted and that I, and the poems, are treated with respect.

I have since submitted the book to a few other presses and there has been tentative interest so maybe it might appear at some point.