Wombwell Rainbow Interviews

I am honoured and privileged that the following writers local, national and international have agreed to be interviewed by me. I gave the writers two options: an emailed list of questions or a more fluid interview via messenger.

The usual ground is covered about motivation, daily routines and work ethic, but some surprises too. Some of these poets you may know, others may be new to you. I hope you enjoy the experience as much as I do.

M.J. Arcangelini

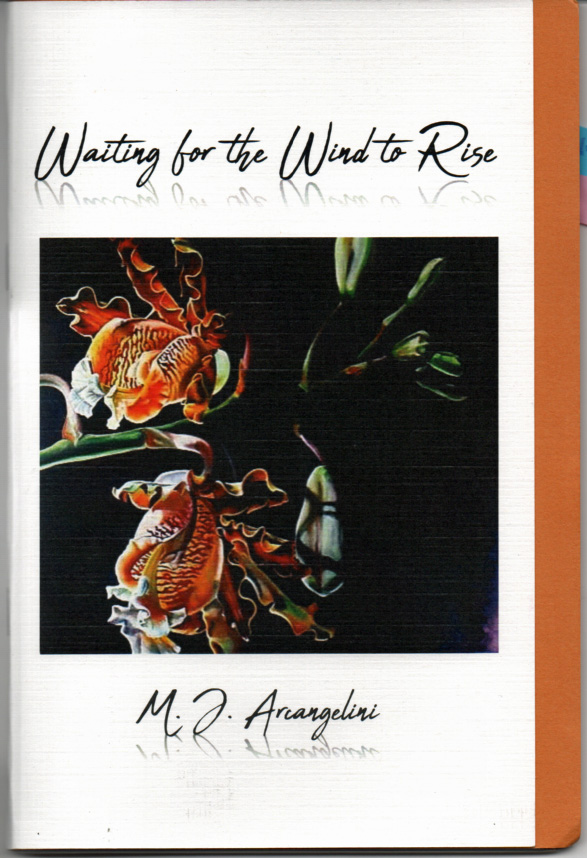

was born 1952 in western Pennsylvania, grew up there & in Cleveland, Ohio. He’s resided up and down the west coast since 1973 and currently lives in west Sonoma County, CA. His work has been published in a lot of little magazines, both in paper and online (including The James White Review, RFD, BEAR Magazine, Whisky Island, Taproot, ArtCrimes, Ev’ryman, Splitw*sky, Jonathan, Callisto, Rusty Truck, The Ekphrastic Review, The Gasconade Review) and a dozen anthologies. He is the author of the full length poetry collection “With Fingers At The Tips Of My Words” from Beautiful Dreamer Press (2002) (http://www.beautifuldreamerpress.com/ ) and 2 chapbooks “Room Enough” (2016) and “Waiting for the Wind to Rise” (2018) both from NightBallet Press (http://nightballetpress.blogspot.com ). A third chapbook “Pawning My Sins” is set to be published in August 2019 by NightBallet Press and a full length collection is pending in 2019 from Stubborn Mule Press. Arcangelini maintains an occasional blog with memoirs and poems at https://joearky.wordpress.com/ In 2018 Arcangelini was nominated for a Pushcart Prize.

The Interview

1. What inspired you to write poetry?

I started writing poetry at 11. It was the death of my paternal grandfather which inspired the first poem I wrote outside of school. Several months after my grandfather died, I woke up in the middle of the night, got pencil and paper from the desk next to the bed, and wrote a poem about him. I then fell back asleep. When I woke in the morning the pencil was jabbing me in the side and there was a poem in my bed. That was the first poem I ever wrote which was not written for a school assignment but instead came out all by itself. I’ve been writing ever since. I wish I still had that poem but it has been lost.

- Who introduced you to poetry?

A nun in Catholic grade school when I was 10 or so. We were studying poetry so the nun would have been the one introducing me to it. I wrote a few for school assignments and got praise and good grades for them and thus was encouraged to continue.

- How aware were you of the dominating presence of older poets?

Not as aware as I used to be, although at my age there aren’t as many living older poets as there once were. The Beats, especially Ginsberg and Gary Snyder, who I began reading in my mid-teens, continue to be a dominating presence for me through both their own work and as the progenitors, along with Bukowski, of the “outlaw” poets whose work I most enjoy today. d.a. levy and the poets who gathered around him in Cleveland in the 60s have long been part of my awareness. Of that group Tom Kryss, D.R. Wagner, and Kent Taylor are still with us and still producing inspiring work. Robinson Jeffers’ presence never seems distant, his work continues to influence and guide me as it has since I first discovered him in my late teens. Then there are Blake, Rimbaud, and of course Walt Whitman, whose call to the open road, both literal and metaphorical, preceded Kerouac’s by a century and continues to echo within my work and awareness to this day.

- What is your daily writing routine?

Morning is the purest time for my writing, I get up early, anywhere from 4:30 to 6:00 AM. My time from then until I have to get ready for work is wholly my own and mostly dedicated to writing. On weekdays most of my energy goes to the job, where I do legal writing. In the evenings and on weekends I go back and forth between writing and doing other things like yardwork, meals, laundry, etc. And the writing itself alternates between poems, letters (I still write real letters to people), and memoirs. I am usually working on at least one of each at any given time, with 3-5 poems in process being pretty normal.

- What motivates you to write?

The act of writing itself motivates me. I am not so much motivated as compelled to write. Perhaps there is an ego satisfaction at the core of it; thinking that what I have to say, to observe, to declaim, might have value to someone else. Pure egotism, as Whitman might have had it. Maybe it is greed. Diane Wakoski writes of “the greed of all poets / wanting the luxury of a life dedicated to writing words.” [Wakoski “Greed Part 2: Of Accord & Principal”] Perhaps I am simply greedy for self-indulgence. And Robinson Jeffers in “Apology for Bad Dreams” speaks of writing his poems as a way “to magic / Horror away from the house” by placing it instead within the safe confines of his work. I believe I do some of that myself, especially in the poems about madness, death, and suicide.

- What is your work ethic?

I’m not sure what you’re looking for here. The hard work I often put in on my poems is its own reward when the poem finally settles into that space where I feel it is finished. Just as the poems which come easy, nearly whole from the start, are simply a gift borne out of the hard work put into previous poems that paved the way.

- How do the writers you read when you were young influence you today?

When I started writing poetry, and for quite some time, everything I wrote showed the influence of Edgar Allen Poe. Strong rhythms, rhymes – it just seemed like the way poetry was supposed to be written. I must’ve been exposed to other poets during those years in school but no other one influenced me as much as Poe until I ran into e.e. cummings. He was so completely the opposite of Poe that it threw me into a tailspin. As far as influencing me today, it is only in spirit that Poe and cummings continue their influence. I believe that very little remains in my current poems of their overt influence. After them I discovered the Beat poets, then Charles Bukowski, Arthur Rimbaud, William Blake, Robinson Jeffers, and d.a. levy all in my mid-teens and all of whom continue to influence me today in one way or another.

- Who of today’s writers do you admire the most and why?

John Dorsey is someone I admire. He has managed to find a way to live as a fulltime poet/writer without compromising the integrity of his work. His poems are always well worth reading. I’ve long admired A.D. Winans, Neeli Cherkovski, and Andy Clausen who are also always worth reading and each provides a living touchstone with the Ginsberg/Bukowski generation. Then there are a whole group of poet/publishers for whom I not only admire their poetry but am in awe of their work as publishers and promoters of other people’s poetry. Among these are Dianne Borsenik, John Burroughs, and Jason Ryberg, but there are others as well.

- Why do you write?

I’ve questioned why I write over the years but have never come up with a good answer, an enlightening explanation. I just do. It is what I do. Good or bad it is who I am. I don’t really write for publication, or very seldom, even though that recognition can be nice. I would write even if I never got published, and did for years. I don’t write for acclaim or awards. I can sometimes write to please a lover or a friend, but most often it is only to please myself.

- What would you say to someone who asked you “How do you become a writer?”

Start writing. Either you is or you ain’t.

- Tell me about the writing projects you have on at the moment.

I’ve been polishing up a set of poems that came out of my open heart surgery in 2012 which I’m hoping to get published somewhere as a chapbook. I’m pulling together a full length manuscript for possible publication in 2019, and picking out poems to submit for a third chapbook to be published by NightBallet Press in August 2019. I don’t write groups of thematically linked poems nor conceive my poems with books in mind so there really are no grand projects in the works. The heart surgery poems came organically out of that experience; I did not set out to write a set of poems on a specific topic. My focus is generally much narrower, on each individual poem as it is being written with no thought as to how it might connect to any other.